By David Fleishhacker

The Argonaut, vol. 26, no. 2, Winter 2016

The Winter 2012 edition of the Argonaut contained an article titled “A Pioneer Ancestor and a Journey of Discovery,” which told the story of my great-grandfather, Aaron Fleishhacker, a man almost unknown to his grandchildren (my father’s generation) and their descendants. My research was done primarily to leave, for my own children and their descendants, some documentation about his life and work, which is now possible to discover from the plethora of online resources. I discovered a man of remarkable talents and energy; not only had he owned a large part of what is today Golden Gate Park, but he also was an organizer of some of the major Comstock mines and a merchant and land speculator in both Virginia City and Carson City.

Yet Aaron Fleishhacker’s story did not end with his death in 1898. In fact, it was his sons, Mortimer and Herbert Fleishhacker, whose names are still remembered by some, not only because of the Fleishhacker Zoo and Fleishhacker Pool (one renamed and the other destroyed), but also for the Fleishhacker Foundation, which still exists, and other civic organizations they and their families helped create. One hundred years ago, Herbert and Mortimer were second only to A. P. Giannini in banking on the West Coast, but beyond that, they were creative investors with interests in lumber, paper, power, and transportation. Their business interests extended from California to Nevada, Oregon, and beyond. They were among the most important businessmen in the West. And then it all came crashing down. It is quite a story, a story I want my children and grandchildren to know. Here is some of it.

Power in the Comstock

As explained in my previous article, it is not certain when Aaron Fleishhacker, later in his life, created the Fleishhacker Paper Box Company or exactly when his sons began working there, but clearly they did this when they were very young. The company’s first appearance in a city directory is 1883, by which time older brother Mortimer was a bookkeeper there — at age 17. Other references say that Aaron founded the company in 1880, when he was 60. This seems likely. At first he purchased or founded the Golden Gate Paper Box Company; soon it was part of A. Fleishhacker & Co and then simply the Fleishhacker Paper Box Company.

Did he do this to initiate his sons into the business world? Mortimer was 14 in 1880 and Herbert only 8, both too young to be actively involved. However, within a year or so, Mortimer was working there, and Herbert would join the company a few years later.

Mortimer is said to have graduated from Boys’ High School in 1880; both brothers apparently finished school before beginning work at a very young age. According to Western Jewry, Mortimer clerked for one year in a wholesale furnished-goods establishment before going to work for his father. The same source says that younger brother Herbert was a bookkeeper there in 1887, at 15 years of age, and that he was educated in the city’s public schools and Heald College. Who’s Who says this was in 1886, when Herbert would have been only 14. It also says he became “manager of the manufacturing end of the business” 18 months later, but it really seems that Mortimer was the manager, while Herbert soon went on the road as a salesman. TIME magazine would, in 1932, tell the story this way:

At 15 Herbert left school to enter his father’s paper box firm as a bookkeeper. Two years later his father died and he and his brother, who was then 23, had to take over the business. Herbert went out on the road selling. He became interested in the mills which supplied the paper for his boxes, found that one was for sale. He and Mortimer raised money from friends and a quick turnover left them with a $300,000 profit. This was invested in power and other mills.

That story has been reprinted in various forms many times, and was certainly believed by the brothers’ descendants, but it is not correct in several particulars. Aaron died in 1898, when Mortimer was 31 and Herbert 25, so they did not “take over the business” at their father’s death. More likely they slowly took over the company as he aged and they grew in ability. So one wonders if the money raised for purchase of an Oregon mill came from “friends” or from their father; the latter seems more likely, as the amount to be raised would have been beyond what two young men with limited business experience could amass so early in their careers. Information about Oregon mills (see below) implies that the story of the $300,000 windfall dates from around 1887 or 1889. In a puff-piece about Herbert, written when he was an active businessman, the story describes the purchase of a tract of land, not a paper mill.

Whatever the facts, a profit of $300,000 was a remarkable achievement, one that must have suggested that investment was a far better road to wealth than running a paper-box factory. Investing, not operating a store or daily business, had allowed their father, Aaron, to amass wealth.

It has been difficult to uncover details of this transaction or subsequent ones that involved paper mills. Many sources provide different versions of the creation of the first paper mills in Oregon. The Crown Columbia Paper Company’s history claims that Henry Pittock created it to supply newsprint for his Portland newspaper, The Oregonian, in 1883, and that the mill burned down and a new facility was built in 1886. Was this the reason that Herbert could make a killing at this time, buying a paper mill that had just burned down? There is no question that the brothers were associated with Henry Pittock, for later, in 1912, they built the “Pittock Block” in Portland, a large and handsome building that still stands today.

The Crown Company and Columbia River Paper Co. merged in 1905, and that company eventually merged with the Zellerbach Company, which by then also included the Floriston Paper and Pulp Company, discussed below. Herbert was an officer of Crown Columbia Paper & Pulp Co. for decades, and Mortimer filled a similar role at Crown Willamette. The mergers and restructuring of these various companies could have involved purchases and sales among insiders in such a way that the original investors made a tidy sum.

In 1899, a newspaper article headlined “Cheap Power for Comstock” explained how Donner Lake and the Truckee River would be dammed by a group of San Francisco and Chicago capitalists. “The new company was organized with a capital of $2,500,000. Its officers are Mortimer Fleishhacker, president; S. D. Rosenbaum, vice-president; Herbert Fleishhacker, treasurer and secretary.” S. D. Rosenbum was the husband of the Fleishhacker brothers’ sister Emma. Most of the other investors were also relatives by marriage: S. C. Scheeline was Belle Fleishhacker’s husband, and Ludwig Schwabacher (who would soon be the manager of the Floriston Paper and Pulp Mill) was their sister Carrie’s husband.

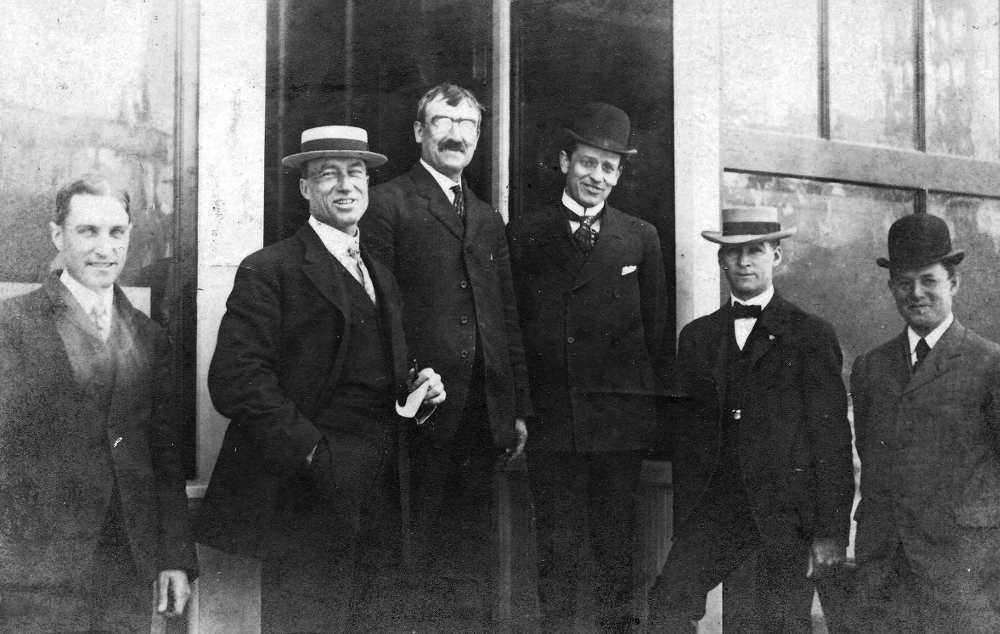

Mortimer (far right) and Herbert (third from the right) are seen at the Bismarck Café in this undated photo. The Bismarck was a huge restaurant in the Pacific Building, described at the time as the “largest concrete building in the world.” It was constructed in 1908 on Market and Fourth Streets and survives today. But the San Francisco restaurant was quite ornate, so this rustic setting may have been the café of the same name created in 1905 for the Lewis and Clark Exposition in Oregon.

The brothers had raised, somehow, $2.5 million to finance these enterprises. Mortimer was 33 and Herbert was 27. It must have been through their previous financing of similar enterprises in Oregon that they had acquired the know-how and the connections to do all this; certainly, managing a small paper-box company in San Francisco could not have given them enough background in finance. Or had Aaron been involved in these plans, too, before his death in 1898?

According to the Truckee Donner Historical Society, “In 1900 the Floriston Pulp and Paper Mill was built where Interstate 80 now passes across the river from the town of Floriston. The existing town of Floriston was a company-built and operated town, with most of the houses constructed in 1900. The paper company operated its own flumes, an aerial tramway in Coldstream Valley, and its own railroad up Alder Creek and into Euer Valley in the late 1920s. Due to the acid pollution that the paper dumped into the river for 30 years, the paper mill closed in 1930.”

Surprisingly, the flume can still be seen today along Interstate 80, as can the old powerhouse, which still operates. According to a roadside marker, the Floriston Mill was one of the largest paper mills in the country at that time, producing paper used to wrap fruits and vegetables for shipping east. In that regard, it was vital to the California farming industry for the first three decades of the century.

As to the power mill, the following tribute can be found in My Memories of the Comstock by Harry M. Gorham:

Two active young men, intelligent, ambitious, and engaged in the manufacture of paper boxes, paper anything, in San Francisco, had started up a power plant on the Truckee River at a little town named Floriston some twenty miles above Reno. This little plant was to make paper pulp for use in their San Francisco business. They found that having developed enough for that purpose they had a good bit of surplus power, and that the art of distribution had been so far perfected as to enable them to carry power to Reno and even into Virginia [City], Gold Hill, and adjacent territory. . . .These two men were Mortimer and Herbert Fleishhacker. I hold both as particular friends of mine.

On old maps, one can still find a place called Fleish, where the power plant was constructed in 1904. While the power plant is still visible, the railroad station there was abandoned in 1938. However, for any user of a GPS device, the name exists, even if the settlement does not; one can actually find youtube videos of trains passing through the non-existent Fleish.

And, as they did so often, the brothers became involved with other companies whose operations were related to power production. The Truckee River Chronology notes that “FP&PC was owned by the Fleishhacker banking and investment firm of San Francisco, an entity which also controlled the Reno Water, Land and Light Company. Of particular interest is that Mr. Mortimer Fleishhacker served as President of the Truckee River General Electric Company in the early 1900s.” Herbert became president of the Reno Traction Co. Both were still major investors in the Oregon paper mills. Floriston was just one, and possibly the largest of, their paper/ hydroelectric interests. The Fleishhacker Paper Box Company still existed, but it had led to much greater things.

The Floriston Pulp plant created environmental problems for years. Lawsuits over pollution in the Truckee River were a constant problem for the paper mill and downstream water users. There were other legal issues, as well; in 1905 a government project was begun to construct a dam at Lake Tahoe for irrigation purposes, and that threatened the water supply for the Floriston mill. According to the San Francisco Call (August 1, 1905), “It has been repeatedly suggested that the Government purchase the big dam owned by F. [sic] Fleishhacker, the millionaire owner of Floriston Paper Mills. The Government offered Fleishhacker $100,000 for his dam and water rights, but he refused to accept it. . . . It is reported that Fleishhacker has said the Government will have a lawsuit on its hand if it attempts to draw the water away from its natural course.” The brothers had both made a mark by this time, but much greater things were in store.

By 1904, Mortimer had also become president of the American River Electric Co. In 1905, Herbert, Mortimer, and nine other investors incorporated the Central California Traction Company; this company owned the right of way for an electric line in Stockton and planned to build the line to Lodi, eventually extending it to Sacramento, Modesto, and the San Joaquin Valley.

Now that both brothers had become wealthy in their own right, it was time to start families. Mortimer married Bella Gerstle, daughter of the late Lewis Gerstle (who had, with Louis Sloss and others, created the Alaska Commercial Company) in San Rafael on Oct. 12, 1904. Herbert married May Greenebaum on August 9 of the following year; her father was Sigmund Greenebaum, manager of the London Paris and American Bank, which consolidated with the Anglo-California Bank in 1909.

There is an interesting story that has come down in the family about Bella. Daughter Eleanor told author Irena Narrell that Bella had confided to her, shortly before her death, that she had been in love with someone else when she married: Dr. Charles Levison, her sister Alice’s brother-in-law. Bella’s marriage seemed entirely successful, but according to family tradition, Bella began to suffer from depression about a decade into the marriage and was advised to consult a psychiatrist, a bold step at the time. The psychiatrist advised her that, as the wife of a wealthy businessman with little to occupy her time, she should take up a hobby, and this advice resulted in her reviving a youthful interest in painting. She had a small studio in her house on Pacific Avenue in San Francisco and another at the family estates in Woodside; many descendants own portraits done by her. The psychiatrist who made this suggestion has always been said to have been Carl Jung.

By the spring of 1906, both brothers had made enough money from their Oregon and Nevada enterprises to be looking around for other investments. They became involved in some big plans. On April 10, the San Francisco Call announced the creation of the West Coast Life Insurance Company. Mortimer (and Mark Gerstle, Bella’s brother) would be among the directors. Then, on April 15, an article announced that a group of capitalists headed by Ignatz Steinhart and the two Fleishhacker brothers, and including Lieutenant Governor Anderson and Mark L. Gerstle, had incorporated to build an opera house “which will equal any in the world” on Post and Powell, at a cost of $800,000, and a seating capacity of 3,000 people.

Note the date. The great earthquake and fire occurred a few days later, on April 18, and ended these plans. Yet bigger enterprises would soon eclipse everything the brothers had done so far.

Expanding Investments

The earthquake and fire didn’t seem to slow down Mortimer or Herbert at all. A week later, on April 23, 1906, the San Francisco Call ran this ad: “Temporary offices of A. Fleishhacker & Co., Truckee River General Electric Co., American River Electric Co., and Floriston Commercial Company, 2418 Pacific ave., near Fillmore.” Mortimer’s home had temporarily become the office for those many enterprises. In a few months, the offices were back downtown; a news ad on July 4 in the San Francisco Call stated, “ROOFERS — Will sublet roofing contracts to reliable roofers or give steady employment to A1 men. A. Fleishhacker & Co., Grant ave. and Bush St.”

By September 30, Herbert was showing the first signs of an interest in living well. “The Hovey Boushey Company report the sales of the following cars for the week: Herbert Fleishhacker, Henry Denham, General MacArthur, M. Feeder and Dr. O. C. Josslyn, Pope Toledos . . .” The Pope Toledo was the most expensive car manufactured by the Pope Motor Car Company, which existed only between 1903 and 1909. General MacArthur was Arthur MacArthur, father of Douglas, the highest ranking general (three stars) at that time, just back from Manchuria, and commander of the Pacific Division.

It is difficult to discover the roles each brother played during the next decades because Herbert, the flamboyant brother, was often quoted or mentioned in articles that, one suspects, were shaped by his own input. Mortimer was less often profiled or quoted.

In 1907 Herbert went to work for his father-inlaw, Sigmund Greenebaum, head of the London, Paris, and American Bank (which had opened in San Francisco in 1885 by taking over the private bank of Lazard Freres – an ironic circumstance in light of Herbert’s confrontations with the Lazard interests many years later). In January of that year, the Call reported, “One of the largest deals known to local financial circles since the April disaster [the earthquake and fire of 1906] is about to be consummated in the coalition of the interests represented by the Fleishhackers, the London, Paris and American Bank and the San Francisco Coke and Gas Company.” It was an alliance that would “bring power from the Truckee [River] and sell it in San Francisco,” becoming a “formidable rival of the trust that controls large power plants in Northern California.” Shortly, the bank merged with the Anglo-Californian Bank, and Herbert became vice president and manager. The bank reorganized as a national bank in 1908. Herbert was elevated to president after Greenebaum retired in 1911. The bank experienced its largest period of growth at this time and was one of the largest banks in the West because of Herbert’s aggressive management.

Meanwhile, Mortimer became president of the Anglo-California Trust, which appears to have been a spinoff of his brother’s bank, handling the savings of depositors while the parent bank handled investments. Banking laws did not allow banks to combine services at this time. The Anglo Trust merged with the Central Trust Company in 1911 and with the Swiss-American Bank in 1912, growing almost as large as its parent bank by the 1920s. In a few years, the banks would be across the street from each other at Market and Sansome Streets (where the shell of Herbert’s bank still stands as a forecourt to the Citigroup Center).

Eventually, the two banks became one. At this point, according to TIME:

Herbert is president of Anglo & London Paris National Bank, with $166,000,000 in resources and $113,000,000 in deposits. Mortimer is president of Anglo-California Trust Co., diagonally across the street, with $81,000,000 in resources and $76,000,000 in deposits. Each is a vice president of his brother’s bank. Both banks have prospered; their solidity has never been questioned. Hence when last week San Francisco heard that the two banks will soon be merged there were no whispers of “taking over” or “just in time.” It was accepted as a move towards economy and perhaps preparation for statewide branch banking under the provisions of the Glass Banking Bill. Friends recalled that for a dozen years the Fleishhackers have contemplated in leisurely fashion the day when they would bank not as neighborly brothers but in one institution.

In addition to banking, both brothers had been busy with other all sorts of other enterprises, as well. In 1906, they sold their interest in a railroad line from Reno to Sparks, Nevada for $200,000, and in October, an Eastern syndicate purchased Reno Power Light and Water, the Truckee River Electric Company, and the American River Company for a reported $5 million.

That same year, the brothers continued to invest in electric power by incorporating the Great Western Power Co., which became and remained northern California’s second largest power company, until it was sold to PG& E in 1930. Mortimer was president and Herbert vice president. The major project of the company was Lake Almanor, named for the daughters of Guy Earl, who built the dam there on the Feather River, flooding Big Meadows to feed the generators at the Big Bend powerhouse.

According to Jessica Teisch’s articles, “Great Western Power: ‘White Coal’ and Industrial Capitalism in the West” and “The Drowning of Big Meadows” (the best available histories of the company, but written from the perspective of someone who excoriates capitalist monopolizing of natural resources):

By integrating regional industries into an extensive urban-rural web, GWP served as one prototype of the twentieth century’s vertically integrated, multipurpose corporations. . . . GWP fortified its position in San Francisco in 1911 by purchasing the San Francisco distribution system of the City Electric Company, which had been incorporated five years earlier by the Fleishhackers. . . . The company transmitted energy from its Big Bend power plant along a . . . steel-tower transmission line 165 miles in length to Oakland. From there, power shot through an underwater transbay cable to a landing at Folsom Street in San Francisco. . . . The Big Bend-Oakland lines passed through Oroville, Marysville, and Sacramento en route to the San Francisco Bay. On the way, GWP served mining and agricultural customers and industrial users, such as United Railroads in San Francisco and a large cement plant in Contra Costa County. . . . The company acquired small independent electric companies in San Leandro, Sacramento, and Half Moon Bay. In 1911, after conducting an electric light rate war against the Sacramento Electric, Gas, and Railway Company, GWP received a contract for lighting the state capitol. With special permits granted by the state Railroad Commission, GWP circumvented restrictions of the Public Utilities Act of 1911 and extended its business into Solano, Napa, Sonoma, and Marin counties.”

Teisch also wrote: “With Guy Earl, Mortimer started Montana Consolidated Oil Company and acquired more than 16,000 acres of land on oil in Montana.” There were some discoveries of oil in Montana in 1919, but there is no evidence of a company with this name.

Previously, in 1907, the brothers had organized the City Electric Company, which had a steam plant in North Beach (supplanted by power from GWP later, one must imagine). It was another family enterprise: the directors were W. Arnstein, H. Fleishhacker, M. Fleishhacker, M. L. Gerstle, A. Mack, J. J. Mack, (the last three were Mortimer’s wife, Bella’s, in-laws), S. C. Scheeline, L. Schwabacher, and Sig. Schwabacher (the last three were Mortimer and Herbert’s in-laws). The head office was at 347 Grant Avenue.

They became involved in still other enterprises. Central California Traction’s beginnings were in 1902 as a streetcar service in Stockton, but electric interurban passenger service to nearby Lodi began in 1907 as ownership was passed to Herbert and Mortimer. Further expansion to Sacramento was completed in 1910, with both passenger and freight services offered over the 53-mile line.

Back in Oregon, in 1911 the Klamath Development Company was incorporated with $2 million of stock; there were five directors, two of whom were the Fleishhacker brothers. In Klamath Falls the remnants of Fleishhacker Street and Mortimer Street still intersect; Herbert Street is on the other side of a waterway. Herbert (or, actually, the Klamath Development Company – Herbert was never one to distinguish between personal and company ownership) would buy the Harriman Lodge on Pelican Lake, where he could entertain wealthy businessmen from the East Coast. The company also owned large farming and timber tracts, mill sites, and the town site of Merrill. In addition, it operated the majestic White Pelican Hotel, famous in its day, which burned down in 1926.

The same year their mother, Delia, purchased and wrote a contract for alterations and additions to the “Old Moulton place at Fair Oaks” from Sarah Winchester (who had been rebuilding her San Jose house since 1884). Delia is not in the San Francisco city directory after 1912, so she must have moved to Atherton as soon as the house was renovated. She would remain there until her death on August 24, 1923.

In 1912, the Call reported that the Fleishhackers had purchased property, 84-by-125 feet, on the south side of Market, near Brady Street (near Gough) for $85,000, planning to erect a building there because they believed there was a great future in that locality when the Twin Peaks tunnel emerged. Streetcar lines on Gough, Haight, and other streets converged here, and there was a rumor that United Railroads would build a terminal nearby. The tunnel actually emerged far to the west, and it is uncertain what the Fleishhackers did with this land.

More importantly, during that same year they organized the Northwestern Electric Company to develop hydroelectric power on the White Salmon River near Portland. Then, in 1916, Mortimer organized the Great Western Electrochemical Company (GWP) in Pittsburgh, CA, to use power available from GWP “at a very reasonable rate” to produce caustic soda and chlorine by electrolysis. In January of 1939, Dow Chemical Company bought this company through a merger, its first. The company was reported to have made a profit of $531,000 in 1938; the merger was described in TIME as costing Dow “almost $12 million in stock.”

In 1913, Honolulu Iron Works contracted for a large sugar mill, for the Calambra Estate, situated 12 miles outside of Manila. “It has recently been acquired by San Francisco capitalists, at the head of whom is E. W. Fleishhacker, [this was incorrect – it was Mortimer], Alfred Ehrman and others. . . . it is expected to have the mill ready to grind the 1914 crop of the estate. It is expected to grind 1,200 tons daily by October of that year.”

During World War I, with their experience in how lumber, paper pulp, and waterpower fit together, the Fleishhacker brothers were part of a group that took over the assets of a Canadian firm, Ocean Falls Company. But their German names led to suspicions voiced in the Ottawa Citizen under the heading “Alien Enemy Control of Canadian Mills”:

An organization called the Ocean Falls Company, in British Columbia . . . passed under German control [and] innocent shareholders, chiefly resident in Great Britain . . . were drained of their life savings to meet the overcapitalization of $4,500,000. Fleishhacker Bros., a German [!] syndicate of San Francisco, ultimately took over the assets of the bankrupt Ocean Falls Co. and floated ‘Pacific Mills, Limited.’ This German combination have been deliberately allowed by the British Government to float $10,154,500 in stock. . . . By that means Mortimer Fleishhacker and Herbert Fleishhacker, with William Pierce Johnson (all of San Francisco) each receive one-third of those 10,154,500 shares in the Pacific Mills, Limited, which they are using to swallow up the Ocean Falls’ inflated capitalization of $6,000,000 together with the pulp mill and the 79,999 acres of pulp timber, water-power and the small oddment of 260 acres freehold.

In an article in 1921, the San Jose Evening News reported, “How rich the Fleishhacker brothers are no one knows. Some say each has an income of $100,000 a month.” That was clearly an exaggeration, for they never amassed enough money to demonstrate anything like that kind of income, and they didn’t spend anything like that. But the published list of enterprises in which they were involved, besides those already mentioned, included (for Herbert) Asia Banking Co. of New York, Baker and Hamilton, California Delta Farms, Del Monte Properties, Morris Plan, Los Angeles Union Terminals, Natomas, Pacific Development, Pacific Mutual Life, United Railroads, Vulcan Fire Insurance, Weed Lumber, and Western American Realty, and (for Mortimer) many of the same companies, as well as Calambra Sugar, Central California Traction, Home Fire and Marine Insurance, Northern Commercial, Realty Syndicate, S. F. Remedial Loan, Tyler Island Farms, and Western Power. It can be assumed that Herbert supplied the information to the writer because he was referred to as the “strictly financial genius of the pair.” Mortimer is not characterized at all.

But before that article was written, both brothers had begun to spend more time on matters that were not strictly business. They had growing families and other interests, and although they remained in business together, they needed to live separate personal and family lives – until many years later, when one had to come to the rescue of the other.

Civic Involvement

Both brothers became involved in civic ventures, but what they did, and how they did it, showed differences in personality that reflected the characterization noted earlier in TIME magazine. “Herbert is heavily built, a noisy dynamo even at play. Mortimer is lean, quiet, takes his fun and work quietly.” For that reason, it is probably best to chart their paths separately from this point on until the real separation was to occur in the 1930s.

Herbert continued to be involved in a plethora of financial dealings on his own after he and his brother had set up their own banks. In 1918, his bank purchased $1 million of Hetch Hetchy bonds, with a $9 million option. He explained to the papers that he had previously been opposed to the project because of concerns about stockholders of Spring Valley Water Co., but his change of heart at this point – if that is what it was – broke a deadlock for the project. Later, this issue created a complex relationship with William Randolph Hearst and his San Francisco Call publisher, John Francis Neylan (later to act as Herbert’s attorney). Hearst was over-extended in 1924, trying to sell small-denomination bonds to readers to help plug a shortfall in funds. Herbert’s bank was a major lender to Hearst, but Hearst’s newspapers were generally opposed to the privatization of natural resources. There was some wheeling and dealing involved to assure that the Call would support the Hetch Hetchy project, and Herbert personally subscribed to about $200,000 of Hearst’s bonds. Without this loan, Hearst might have faced collapse. Then, a few years later, the San Francisco Bulletin, the city’s oldest paper, was sold to Hearst’s Call (creating the Call-Bulletin) by Herbert Fleishhacker, according to the Oregon Statesman. How and when Herbert acquired that paper, if it was he instead of his bank that owned it, is not clear.

Herbert was part of a syndicate (including William Wrigley, John D. Spreckels, and Edward Swift of Swift & Co.) that purchased 23,000 acres in San Diego for $4 million in 1919. His reputation and clout were also instrumental in Samuel F. B. Morse’s purchase of Pebble Beach’s Del Monte properties, including over 18,000 acres and the original Hotel Del Monte, which burned and was rebuilt in 1924.

Herbert was one of the four principal investors in the Dollar Line. He was reported, in Mike Quin’s The Big Strike, to have been one of four officials of the company who between them earned $14 million in salaries and bonuses between 1923 and 1932. Among Herbert’s many problems in 1938 was the failure of that line, which was taken over by the U.S. Maritime Commission; TIME reported that not long after Captain Dollar died and his son R. Stanley took over, “the Dollar Line owed Anglo California some $3,000,000; and of the Dollar stock, the Fleishhackers owned 109,000 shares, the Dollars 93,000.” TIME also reported that the Maritime Commission “listed him [Herbert] among those who milked the Dollar Line almost to extinction.”

Among Herbert’s many enterprises was the Stanford Barn, now part of the Stanford Shopping Center. The history of the Stanford Barn [http://resume.wizzard.com/w1995/stanfordbarn/ history.html] says that in 1916: “At the closing of the Panama-Pacific International Exposition in San Francisco, Herbert Fleishhacker, Sr. acquired a prize exhibition herd of Holstein cows. For his Carnation Milk Company Fleishhacker leased over 200 acres of land surrounding the winery for grazing and hay land and converted the idle winery into a milking barn. This was convenient for Fleishhacker since he also summered in nearby Atherton and the lease provided a good place to keep his riding horses.”

The Palo Alto Stock Farm, of which he was a director, must have been an offshoot of this. But it was also a holding company, as it was named in some of the suits against Herbert later in life. Herbert’s business interests were clearly entwined with local politics. In 1920, he was a delegate to the Republican Convention in support of Hiram Johnson, the progressive California governor. More significant was his association with “Sunny Jim” Rolph, San Francisco mayor from 1912 to 1931, and governor from 1931 to 1934. He was a major source of campaign funds for Rolph, and Rolph repaid him by not only supporting the Hetch-Hetchy project and similar business ventures that involved Herbert’s bank, but also by appointing him to the San Francisco Park Commission in 1919. (Herbert became president in 1922, serving until 1940.)

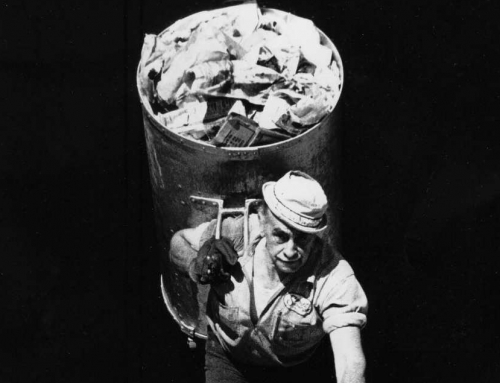

“Little Puffer” steam train at the zoo. Donated to the zoo by Herbert Fleishhacker in 1925, the miniature train ran in the zoo for 53 years, and then was put in storage. Through a generous grant from the Richard and Rhoda Goldman Fund, the train was repaired and restored. In 1997, it returned to delight zoo visitors. Courtesy of the San Francisco Zoo.

As President of the Park Commission, a role he obviously relished, Herbert was creator of what became known as Fleishhacker Zoo and Playfield and the Fleishhacker Pool. In 1921 he gave to the playground in Golden Gate Park a “kiddie coaster” (an inclined plane of concrete, down which children could ride on carts, still operating early in my childhood) and paid to have the carousel organ repaired. In 1922 he gave the carousel in Golden Gate Park to the city, as a memorial to his fatherin- law, Sigmund Greenebaum (a fact long forgotten and unmemorialized). These were early signs of what he had in mind. In the next 20 years he was the force behind the creation of the Fleishhacker Pool, Fleishhacker Playground, and Fleishhacker Zoo.

The playground was named for him by the Park Commission over his objections, he claimed. That name has vanished, yet the playground, rebuilt and remodeled frequently, still retains another carousel he either purchased or arranged to be purchased. The miniature train he donated, “Little Puffer,” once bore his name but was retired, then revived and renamed for later donors. The Mother’s House, which he and Mortimer built in honor of their mother, Delia, endures.

The zoo was renamed the San Francisco Zoo shortly after it opened its new WPA facilities in 1940. Herbert requested the name change because the newly built facilities went far beyond anything he had overseen. Although he may have been more of a promoter than a major donor, he did provide funds to purchase land and animals for the zoo, hire George Bistany as the zoo’s first director, and support the zoo in various ways, although funds mostly came from the city and the WPA.

The Fleishhacker Pool bore his name until it closed in 1971. It was usually referred to as the largest heated swimming pool in the world (1,000 ft. in length). The last evidence of it was the original pool house, still called the Fleishhacker Pool house after the pool was closed and filled in for a parking lot. The deteriorating pool house was briefly used as Janet Pomeroy’s Center for the Handicapped, then as a pottery studio and children’s craft camp, and then abandoned. It became an eyesore occupied by derelicts, until it burned on December 1, 2012, and had to be torn down.

Herbert may have promoted the creation of these large recreational facilities because of business connections with the Spring Valley Water Company; as one writer put it, “Whether he was acting with smart business sense, or if he truly wanted to provide a place of civic benefit we’ll probably never know. But as a result of his efforts as commissioner of the San Francisco Parks commission, Fleishhacker spearheaded the campaign to construct the pool. The direct beneficiary of the massive public project was the Spring Valley Water Company. The total cost of the project was estimated at $1.5 million – even for the roaring twenties, this was a huge sum of money.”

Herbert’s summer residence was at Lake Tahoe, not far from the area where he and his brother had created the Floriston mill and powerhouse. The Lake Tahoe house was one of the early estates on the lake; and Herbert and his son, Herbert Jr., were both proud owners of racing boats on the lake. In “The Saga of Lake Tahoe” by E. B. Scott, there are numerous references to Herbert’s activities at the lake:

By the summer of 1925 the Bliss interests, a name that had been synonymous with the development of Tahoe since 1873, were bowing out of the picture on the western side of the lake. A group of San Francisco capitalists, Bruce Dohrmann, Milton Esberg, John Drum and Herbert Fleishhacker, Sr., in combination with the Linnard Hotel Interests, assumed management of the Tahoe Tavern Properties. On June 30 of the same year, Southern Pacific and the Blisses reached an understanding – an annual payment of one silver dollar.

The Bliss family turned over the narrow gauge railroad to the Southern Pacific on a 99-year lease. In return the Southern Pacific agree to convert the line to standard gauge and offer over-night service between San Francisco and Tahoe City. . . . Winter train service, primarily to Truckee but also to Tahoe was known as the Snowball Express. Because of competition from the new service [highways] . . . it was discontinued in 1942 and the rails were torn up and used for scrap iron in World War II.

In the summer of 1905 Fredrick C. Kohl of San Francisco [he was a partner of Sloss and Gerstle in the Alaska Commercial Company] purchased the Crocker home at Tahoe…. In 1926, Herbert Fleishhacker, Sr. San Francisco capitalist, bought the Kohl estate together with extensive sections up Blackwood canyon. An enclosed swimming pool in the lake and shoreline cottages were added, along with two speedboats to complement the 60- foot cruise Idlewild originally built for Kohl. The new additions in the marine line were for his sons, Herbert, Jr. and Allen.

During the 1930s, the Everts Mills family acquired the Fleishhacker interests at Idlewild. Much of the original holding was subdivided and the old home, with its north wing, was removed. Among a few surviving family memorabilia are photos and albums of Herbert’s house at Lake Tahoe, including signatures of his many guests, including a picture of Herbert and Will Rogers sitting on the running board of a large auto. Now and then, items he or his family once owned show up for auction at eBay or on other websites. Below is one example:

Up for auction is an impeccably-crafted muskrat fur throw/blanket from a historical San Francisco family, at his former Hillsborough, California estate . . .The owner of the pelt, Herbert Fleishhacker Jr., former Stanford University football star, Navy commander, banker (VP of Crocker-Anglo National Bank), insurance executive, and president of the National Retriever Club (black labrador breeder) . . .

Scandal and Loss

The circumstances regarding Herbert’s problems and eventual bankruptcy are clouded by the fact that these events were never discussed by the families and were essentially hidden from their grandchildren. Herbert’s decline resulted from a series of lawsuits, the first of which was instituted by members of the Lazard family in the early 1930s. The Lazard family claimed that Herbert had mismanaged or appropriated funds from their investments 20 years earlier. Suits from others claiming similar mingling of Herbert’s personal funds with bank funds followed, but most of the story was not reported in local papers at all. The accounts that do survive from TIME magazine, when Herbert lost his last appeals after half a decade of litigation, must be taken with a grain of salt because of the racist bias displayed in this excerpt: “A big, heavy-jowled Jew of 64, Herbert Fleishhacker made a small fortune in wood, paper and power mills.”

The Lazard family had once controlled the Anglo London Paris (which later became the Anglo Bank), presided over by Herbert’s father-in-law, Sigmund Greenebaum. The Lazards and their descendants remained stockholders after Herbert’s assumption of the presidency in 1911. In 1919, Herbert and the bank were involved with the Barde family of Portland in a purchase of surplus steel that eventually netted a large profit.

According to a later record:

In 1931 Etienne Lang, a member of the Lazard family and related to all of the plaintiffs herein, began an investigation of matters in which the Anglo Bank and Herbert Fleishhacker had acted as agent for the Lazards. . . . Lang, as agent for plaintiff stockholders, caused to be delivered to the chairman of the board of directors of the Anglo Bank a demand that suit be forthwith instituted on behalf of the bank to recover all profits received by Herbert Fleishhacker in his transactions with the Bardes. The board of directors passed a resolution refusing to take action. This suit was filed on December 5, 1934.

Simply put, the suit resulted from the fact that Herbert had profited personally from this transaction, which the court found to be a violation of his duty as an agent. Judge St. Sure found that “Herbert Fleishhacker violated his trust to the bank and its stockholders; that a part of the consideration for the loans of the Anglo Bank to the Bardes was the participation by Herbert Fleishhacker with them in the profits of the steel deal; that Herbert Fleishhacker made a private profit for himself in the discharge of his official duties.”

Greater troubles were to follow, as the Lazard family and its descendants now investigated another transaction in which they had relied upon Herbert and the bank to represent them. This involved lands in Kern County, which were part of or adjoined the Lost Hills oil field. In this case, the same judge found that:

. . . in 1913 he had received an offer of $2,000 an acre for 80 acres of the specific property later sold. This offer was never reported to the owners and appellant Herbert Fleishhacker denied that it was ever made. Correspondence subsequent to the 1915 sale but before the 1917 sales tended to show concealment of the facts known at the time of sale, and thereafter disclosed by the subsequent developments.

In other words, Herbert was accused of having sold 150 acres of oil land for well under its real value and not communicating all the facts to the Lazard interests. Of course, at this time World War I was raging in France, and communications were not simple or regular, nor was it proven that Herbert personally profited from this concealment, but “proof of financial gain to the wrongdoer is unnecessary in an action of fraud.” And “the evidence supports the finding that the representations . . . were false, known by appellants to be so and consequently were fraudulently made.”

This also occurred during a time when the Dollar Line was in serious financial trouble, and Herbert owned as much of that line as anyone. He was later accused of having “milked” the firm, helping to cause its demise, but there is little evidence that he suffered any less from the Dollar Line’s failure than others; the accusations may have stemmed from all the unfavorable publicity that surrounded him then.

Whatever the truth of all these matters, the result was bankruptcy for Herbert and embarrassment for Mortimer, who first assumed the chairmanship of the Anglo Bank board when Herbert was forced out, and then, one year later, resigned from the bank, along with his son (my father) and his nephew, Leon Sloss. Herbert’s troubles had not ended, however. In March of 1940 a federal indictment charged him with misappropriation of $55,000, accusing him of withdrawing money for his own use without authorization from a Pacific Mail Steamship Company account in his bank. The outcome of this case is not certain; perhaps he was exonerated in this instance (as his nephew Jimmy Schwabacher recalled). In any case, he would not have had the money to make restitution at this late date.

In a 1944 lawsuit, stockholders alleged that the bank had acted improperly by settling for less than they should have in a compromise with Herbert for restitution. This suit failed: the judges found that the settlement in question was in the best interest of the bank and that Herbert was in bankruptcy and thus “there was no possibility of realizing from his estate more than a part of the judgments that had been obtained against him in the earlier secondary suits. Nothing was to be gained by pursuing him further.”

The same court noted that “Following a recapitalization of the Bank, Mortimer Fleishhacker had paid in the sum of $2,590,000 on account of loans in which he had been interested.” It seems clear that Mortimer provided restitution to many or all of the creditors. Given that Mortimer left an estate of $4.7 million (including Green Gables) at his death nine years later, his personal sacrifice in paying off his brother’s debt was substantial, probably around 40 percent of his assets at that time. One must also assume that he supported his brother for the rest of his life.

The close association between brothers had ended. Herbert was not known to or seen by Mortimer Jr.’s children, Delia, Mort, and David, who never were told anything about this. Herbert had earlier been a guest at Green Gables once or twice, for birthday celebrations. (Until he became bankrupt, he had had his own property on Fair Oaks Avenue in Atherton.) But after all these troubles, neither Herbert nor his sons were known to the next generation of the family.

Herbert had three children. My father, Mortimer Jr., liked the youngest, Alan, but never spoke well of Herbert Jr. My impression was that he considered Herbert Jr., a very successful Stanford fullback and something of a playboy, devoted to boating, dogs, and hunting but with no interest in community service. On the other hand, Alan made a decent living by founding the Yosemite Beverage Company at 150 Potrero Avenue in 1947, an enterprise in which he was able to involve his father after Herbert Sr. was forced out of the bank.

Herbert Sr. lived out the rest of his life at the St. Francis Hotel, but it is not correct, as sometimes reported, that he moved there because of his reduced circumstances. For several years after his marriage, Herbert, his wife, May, and eventually their children lived with his mother Delia (and his in-laws, the Scheelines) at 2110 California Street or at Fair Oaks in Atherton. In 1913 he was living at the Fairmont Hotel, but in 1914 he had moved to the St. Francis Hotel; not coincidentally, in 1913, his bank was a major underwriter of the hotel’s bonds, which were used to construct the double-width north wing as apartments for permanent guests. His residence there belies his claim, to some extent, that family life was central to him, as it is hard to imagine what his children’s lives were like growing up in a hotel, in contrast to Mortimer’s life at 2418 Pacific, his wife Bella Gerstle’s home. Herbert died in 1957, four years after his brother.

Like his brother, Herbert was a domino player, and that is supposed to be the reason that an opening play of 3/2 was in some circles known as a “Fleishhacker” or a “Herbie Fleishhacker,” because one cannot score off that play. The game of dominos played in San Francisco clubs (and a few other places) is familiar to all San Francisco players but, apparently, not to domino players anywhere else; rule books for domino games do not include it. A few San Franciscans – at least in our family – still know the name “Fleishhacker” as a domino play, if nothing else.

Mortimer

One of Mortimer’s major interests was the creation of Green Gables, beginning with assembling properties in Woodside in 1909 and in 1911 hiring Charles Sumner Greene, whose work continued there until 1927. Various works by Edward Bosley, Randell Mackinson, and others best document the story of Green Gables. Mortimer later also developed Woodside Heights to east of the town, naming the main road Eleanor Drive for his daughter. He was sued by J. M. Huddart in 1912 for damming Squealer Creek, but this suit must have been settled, because the water from that dam, used on alternate days, was the only source of water at Green Gables until the 1950s.

The wedding of Mortimer’s daughter Eleanor to Leon Sloss at Green Gables, 1925. From the author’s collection.

Green Gables still exists today, one of the last great estates on the San Francisco peninsula. Because of an easement granted to the Garden Conservancy, Green Gables’ 75 acres cannot be divided or changed substantially. Currently it remains a private summer estate shared by Mortimer’s grandchildren and their descendants.

Mortimer was especially busy in business and civic affairs at this time of his life. He was one of the “leading bankers, merchants, and philanthropists” who made up the San Francisco Remedial Loan association (according to the December, 12, 1912 Call) to relieve, with low-interest loans, people who had been victimized by loan sharks. In 1913 he was named as one of four prominent financiers to take over the properties of “Borax” Smith; the company that manufactured Borax would soon be directed by his wife’s relative, Jim Gerstley. Mortimer was part of an organization, “Hands Around the Harbor,” to boost business in both Oakland and San Francisco. He was one the directors of the Urban Realty Improvement Company, which developed Ingleside Terraces in 1913. Other enterprises in which he was involved included the California Wine Association, of which he was elected a director. It operated Winehaven (1907–19), a winery and town in Richmond said to be the “world’s largest winery” until prohibition forced its closing. The buildings there still stand, and are currently used by the U. S. Navy.

Meanwhile, the Fleishhacker Paper Box Company was still in business, with offices after the fire at 134 Fremont Street (currently the construction site of the new Transbay Terminal). Herbert and Mortimer were two of the five directors of Fleishhacker Paper Box Company; a third one was brother-in-law Simon Scheeline, sister Belle Fleishhacker’s husband. The other directors were R. E. Wallace and W. J. O’Donnell, and so it remained until 1940, when Herbert’s bankruptcy caused him to leave the business, replaced by Mortimer’s son, who assumed major responsibility for the company after he returned from service in the navy, until it was sold in the 1950s.

Mortimer served on the draft board during World War I, resigning in September 1918 as the war was ending because of a need to attend to business, but he shortly became involved with other matters of public service. He and Gavin McNab were asked by President Wilson to help in the settlement of an ironworkers’ strike in 1917. He was appointed a regent of the University of California in 1918, serving two 16-year terms. In December of 1918, he headed a drive for the relief of European Jews in the aftermath of the war. A list of donors includes his sisters Carrie and Emma, his mother, Crown Willamette Paper, Greenebaum, and Rolph Navigation. (By this time Herbert had become Mayor Rolph’s major supporter.)

In 1919 Mortimer was appointed, along with Archbishop Hanna and Governor James Lynch of the Federal Reserve, to a commission to investigate possible fraudulent practices in connection with the sales of Liberty Bonds. In 1921 he was a member of a conference on unemployment called by President Harding; he was quoted as saying that California was not suffering unemployment to the same degree as the rest of the country.

He was a charter member of the board of International House, Berkeley, from 1929 to 1944. His son and grandson were later both active there, and the library was named for the family in 1968. Another enterprise in which he was involved in 1929 was the executive committee of the Northern California Committee of Herbert Hoover’s European Relief Council. This organization raised money for starving children in central Europe.

No documentation proves this, but in the opinion of his grandchildren, Mortimer suffered a great deal of distress from his brother’s financial collapse, not to mention a large loss of his own assets used to pay off his brother’s debts. He was known to his grandchildren as a kindly but reserved old man whom they saw at weekly dinners, at his home or theirs, or at Woodside. He sometimes took them for chocolate-covered ice cream cones (which he called “bing-bangers”) in Redwood City. He was also remembered for the nonsense phrase “Sic semper tyrannis – du flicka paragoric – tomatoes and shoestrings,” the origins and significance of which, outside of the Latin, are unknown.

Mortimer continued to go to his office almost daily, where his son worked by his side. However, his time was now often spent playing dominoes at the Stock Exchange Lunch Club (now the City Club) or napping. Until late in life, he walked to the club from his home at 2418 Pacific, which may account for his good health, but as age – and embarrassment at the family “scandal” of his brother’s bankruptcy – took their toll, he slowly acquired signs of elderly dementia. He died on July 13, 1953 at age 86, in the same hospital where his great-granddaughter, Jodie Ehrlich, had been born two days earlier.

About the author

David Fleishhacker was born in San Francisco a few days after the completion of the Golden Gate Bridge. He and his wife are descended from California pioneers, and most of their children and grandchildren continue to live in San Francisco. After a decade of teaching in local private schools and in Afghanistan, where he was a member of the first Peace Corps group, he became headmaster of Kathrine Delmar Burke School, a position he held for 25 years. Since retirement, he has been active in local amateur and professional theater and in service to nonprofit organizations (Berkeley Repertory Theatre, San Francisco Symphony Youth Orchestra). A previous article about his family appeared in the Winter 2012 edition of The Argonaut.

Bibliography

Gorham, Harry M. My Memories of the Comstock (1939).

Teisch, Jessica. “The Drowning of Big Meadows: Nature’s Managers in Progressive-Era California,” Environmental History (Oxford University Press), 4:1 (Jan., 1999), 32–53.

Teisch, Jessica. “Great Western Power, ‘White Coal,’ and Industrial Capitalism in the West,” Pacific Historical Review. 70:2 (May 2001), 221–53.

Truckee River Chronology: A Chronological History of Lake Tahoe and the Truckee River and Related Water Issues (a publication in the Nevada Water Basin Information and Chronology Series).