By Deanna Paoli Gumina

The Argonaut, vol. 25, no. 2, Winter 2014

It was the best of times, without a shadow of a doubt. For 16 years, from December 15, 1951, until its closing in the spring of 1968, Paoli’s Restaurant welcomed guests at its Montgomery Street location (at California).

On a “good” Friday night, the bar alone exceeded the weekend revenues for both the main dining room and mezzanine. It was a wild run that received praise for its continental-style cuisine from Holiday magazine, the gold standard for gourmets, who described the clientele as an “unbelievable crush of Montgomery types.” Curt Gentry’s doomsday book, The Last Days of the Late Great State of California,1 pronounced the restaurant as the hottest Friday night spot on the West Coast, where young attractive career girls went “to get a jump on the competition” in the hopes of meeting “Mr. Right.”2 The Paolites, as the clientele deemed themselves, were young, good looking, and the masters of their universe.

Paoli’s captured the euphoric spirit of the 1950s, a time when the country was breathing a sigh of relief after the world emerged from a disastrous world war and before plummeting into the uncertainties of a decade that always seemed on the brink of some dangerous confrontation. The decade heralded a new class of diners who emerged from the American middle class and became the fastest growing sector of a rising food industry.3 It was a clientele whose appetites were whetted on the hard liquor brews of bourbon—America’s whiskey—as well as rye, and the sweetened syrup of Coca-Cola, unless you were Jewish and drank Manischewitz wine. The strong taste of these brews had to be considered as these newly minted American diners nearly anaesthetized their taste buds drinking them, only to proclaim that the food did not taste of anything!

Changing this bourbon-on-the-rocks palate was the challenge that trained chefs and restaurateurs born or schooled in Europe contended with as they sought to encourage the drinking of wine as the perfect accompaniment to fine dining.4

However, it was not until Robert Mondavi’s 1969 Cabernet Sauvignon won top honors at the Los Angeles Times Vintner’s Tasting Event in 1972 that the quality of California wine was heralded as equal to or excelling that of wines produced in France, Spain, Italy, and Germany.5 Even before this event, which would focus the wine world’s attention on the Napa Valley wineries, my parents selected Mondavi’s 1969 Cabernet Sauvignon for my wedding.

The neighborhood that surrounded Paoli’s included some pioneer restaurants that dated to the 1860s, with patrons loyal to Jack’s Restaurant on Sacramento Street and Sam’s Grill on Bush Street. Newer restaurants opened in the 1930s, including The Blue Fox, which specialized in frog legs but had the reputation of being neighbor to the City Morgue on Kearney Street.6 At the upper end of Montgomery Street was Il Trovatore Café, which was renamed Ernie’s by its two young owners and former busboys, Vic and Roland Gotti.7

Paoli’s followed in the footsteps of the newly opened Panelli’s Bar and Grill at 453 Pine Street, which was run by the dapper, silver-haired Joe Panelli and his brother, Roy, who were well known for their Italian cuisine (especially their savory osso buco), as well as selected meats and chops charcoal broiled to order with a tantalizing aroma that stimulated appetites. Panelli’s was already attracting a sizable bar business with its latest drinks accompanied by platters of tasty hors d’oeuvres, and for the after-theatre crowd, there was a banquet room.8

By 1959, Roy Panelli was on his own, breaking away from the Italian-style menu. He opened The Red Knight at 624 Sacramento Street, a venue that combined a “dash of the Edwardian.” As for Panelli’s, it became Ruggero’s in 1967 as Joe retired, handing the baton – or the reservation book – to Ruggero Bertola, one of the finest chefs in San Francisco. Rugerro’s expertise included blending exactly the right ingredients in his veal dishes and Petrale Meuniere; diners would have licked their plates in tribute if social etiquette allowed. Sweet butter, a zest of lemon, and knowing when to flip the clove of garlic out of the pan were the essence of delicacy. Contrary to popular thinking, garlic was meant to flavor the oil, unless it was cut into silvers and blended with ingredients. It was not meant to overpower a dish or to stick to a diner’s taste buds like Velcro. Ruggero ran Paoli’s kitchen for several years, until he opened his own restaurant on Pine Street.

Indeed, competition among restaurants was rampant, but as Joe Panelli said, “there was enough business to go around for everyone.”9 Sensing that they were on the forefront of great change brought about by the end of a world war, a new consumer culture, and the ability to globetrot, there was no doubt in the restauranteurs’ collective thinking that San Francisco was and would always be a restaurant town. Conceived in the chaotic Gold Rush days of hearty appetites and hard drinking, now the city sought to be the equivalent of New York in the breadth and appeal of its restaurants. As in Manhattan, new restaurants would draw the city’s population away from the neighborhood eateries and into a district of financial institutions and banks as they catered to the tastes of those working in the maze of streets that was dubbed “the Wall Street of the West.” Between 1950 and 1960, the number of workers in San Francisco’s finance, real estate, and insurance industries increased dramatically. By 1960, about 70 percent of all Bay Area workers employed in these fields worked in San Francisco’s Financial District, near ing New York City’s statistics.10

Advantageously located at 347 Montgomery Street at California Street, Paoli’s was on the perimeter of the Financial District’s major intersection, a four-way noontime corner scramble of bankers, stockbrokers, insurance agents, attorneys, engineers, and as Herb Caen wrote, “some of the most attractive secretaries” in town.1 With an hour for lunch that for some extended to mid-afternoon, this clientele rushed through the restaurant’s double doors with hungry appetites that were washed down with a quick pick-me-up libation.

Paoli’s opened ten days before Christmas, 1951. My parents were hopeful that the spirit of this festive season would favor them with an opportunity to participate in this new venture, although neither had any formal culinary background or restaurant management experience. My Dad, Joe, had shucked oysters and steamed crabs in the hot cauldrons at a Fisherman’s Wharf restaurant, earning his way through high school. When World War II erupted, he was drafted into the Army, but at a boxing show at Fort Ord in Monterey the C.O., a boxer himself, asked Dad if he would be willing to transfer out of the Army into the Navy and continue to box for the troops. To qualify for a transfer between these branches of the service, Dad had to profess expertise with either deck engines or as a steward in the galley. Claiming knowledge of cooking, Dad joined the Merchant Marines and sailed out of San Francisco on a Liberty Ship that he described as a “sitting duck” against any adversary. His duties as chief steward, he wrote in the black sketchbook he kept as a journal, consisted of “the lowest job of galley man, dishwasher and pot washer and deck scrubber.” He knew that if he failed, he would be transferred back to the Army as a foot solider. As the ship swayed with the winds and rode on the crest of waves, he oversaw the preparation of the daily meals served to the captain and the crew. Keeping tins of this and jars of that on the shelves was no easy task.12

When the war ended, Dad found work at the historic Maye’s Oyster House on Polk Street, and he eventually acquired a modest partnership in the restaurant. Maye’s was owned and operated by Phil Modrich and his family, immigrants from Yugoslavia. Their culinary expertise was cooking a variety of seafood and fish. The specialty of the house was their “Old-Fashioned Oyster Loaf.”13

After five years of working for Modrich, Dad left, eager to strike out on his own. His timing was fortuitous. Within a month of his departure, a disastrous fire consumed the popular Maye’s. Dad had already made the transition to Paoli’s, but his name still appeared on the fire department’s emergency call list for Maye’s. In the middle of the night, a dispatcher called him saying that “your restaurant” was on fire and he was to meet the fire captain at the site immediately. Stunned, my Dad asked whether the fire had started on Montgomery or California Street. The dispatcher quickly responded, saying Polk Street. Relieved but disheartened for his former partners, Dad went to stand on the street amid water hoses and smoldering ashes, consoling Modrich and his crew.

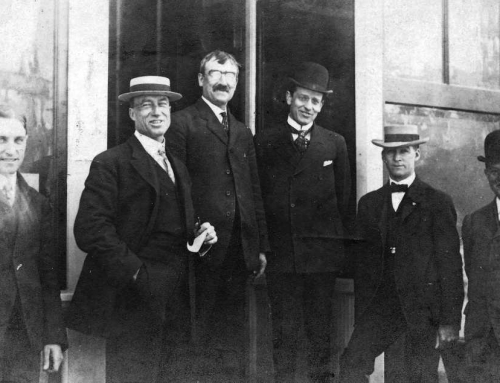

Dad with actor Tony Curtis, who is holding an H.M.S. Pinafore hat worn by the bartenders. Author’s collection.

Paoli’s was at the forefront of a new wave of dining that became known as “continental cuisine.” Taking the best from a variety of cuisines and a step back from the French standard of haute cuisine, continental cuisine was defined in part by décor: heavily starched white table linens; plush leather or vinyl booths that were usually semicircular in shape in red, dark brown, or black hues; and highly polished silver serving pieces. Indirect lighting softened the dining rooms, and flickering candles, a bud vase, and the customary ashtray (a sign of the times which can still be purchased on eBay14) completed the table setting. Although menus were written in the native language of French chefs, cooks, and East Coast restaurateurs whose English language skills were limited,15 their impact intimidated unsophisticated diners with an affront of snobbery. Later, like subtitles in a foreign film, these French culinary terms were translated beneath the dish, enabling diners to order without embarrassment.

“What is the basic difference between French and Italian cooking?” asked Enrico Galozzi, the noted Italian gastronomic expert. He explained, “French cooking is formalized, technical, and scientific. Order Béarnaise sauce in 200 different French restaurants and you will get exactly the same sauce 200 times. Ask for Bolognese sauce in 200 different Italian restaurants and you will get 200 different versions of ragù.”

In The Food of Italy, Waverly Root, the noted food historian, wrote, “most persons think of the French as the great sauce makers; but it was the Italians who first developed this art. The French learned it later from the cooks who came to France in the train of Catherine de Medici. It is a given that in large French kitchens making the sauces is the job entrusted to a specialist, the saucier. In Italy every cook must be able to concoct sauces or he [or she] could hardly cook at all. In France, a sauce is an adornment, even a disguise, added to a dish more or less as an afterthought. In Italy it is the dish, its soul, its raison d’être, the element that gives it character and flavor.”16 Italian cooking, concluded Root, is home cooking – la cucina casalingua, human and light-hearted compared to the formal French tradition that ruled restaurateurs and food critics of the 1950s and 1960s. Decades later, a new generation of dedicated “foodies” would come to embrace this growing preference for fresh, healthy, informal meals.

Continental cuisine adopted a near-military protocol, as the dining room was under the direction of a knowledgeable but often intimidating-looking maitre d’hotel who supervised an entourage of tuxedoed captains escorting diners to their reserved tables and handing them menus. Nothing was left to chance; without reservations, casual diners were turned away—except at Paoli’s, which always found an available table, even if it was a quickly assembled wooden top draped by a white linen tablecloth in some corner.

The meal began with the presentation of a menu as busboys scurried about filling water glasses and bringing sliced bread and butter patties kept chilled in silver bowls with shaved ice. Table service included carts or hand-trays, which were brought to the table loaded with assorted appetizers and presented with great fanfare to the hungry diners, as were the forthcoming entrées, unless the meals were cooked to order in chaffing dishes set ablaze as the diners oohed and aahed. Salads were dressed and tossed at tableside, and soups came in tureens and served steamy. Desserts and coffee followed with their own regimented service. And the coffee service included Sanka, one of the earliest decaffeinated instant brews with the gall to call itself “coffee.” Paoli’s served it for 50 cents a cup.17 This was the drumbeat of upscale continental cuisine dining.

As diners opened the double doors to Paoli’s, they were welcomed into an attractive dining room that under my mother’s decorative eye featured French-provincial decor typical of the 1950s. My mom, Rita, had acquired wallpaper that she had hoped to use at home. Instead, she purchased additional rolls and papered the restaurant walls with it. She rummaged through antique shops, gathering an assortment of copper pots, a vintage clock, and other artifacts that she had hoped would give the dining room a cozy, comfortable, homey look. As a gimmick, a three-foot-high wooden pepper mill especially made for the dining room was ceremoniously used to season the Caesar salads. Three times, the giant pepper mill was stolen by customers and later returned. The gold plaque attached to it stated the most recent prankster’s name and the date that the pepper mill was stolen. It was reported that Sherman Billingsley of New York’s famed Stork Club wanted the pepper mill. The game ended when the last culprit kept the mill.18 Lost but not forgotten, it was replaced by ceramic plates printed with the recipe for Caesar salad, a salad made popular at the House of Murphy Restaurant in Los Angeles, owned by actor Bob Murphy. The story was that Murphy had eaten this salad in Mexico and brought it to his restaurant, putting it on the menu as DeCicco Salad. It consisted of lettuce tossed with imported cheese, anchovies, tossed croutons, garlic, coddled egg, and wine vinegar. One of Murphy’s customers, fellow actor Charles Laughton, renamed it “Caesar Salad.19

Two other features of the young restaurant capitalized on San Francisco’s restaurant tradition: the oyster bar, which prepared salads and seafood dishes to order, and an historic bar, a source of great indulgence made from imported South American mahogany. Oysters were extremely popular throughout the United States. Oysters were served according to local customs, including raw and on the half shell, fried, broiled, roasted, pickled, deviled, scalloped, and barbequed. They were consumed on their own or in soups, chowders, and pastas. While New Orleans boasted of its Oysters Rockefeller, San Francisco’s Chef Ernest Arbogast of the Sheraton Palace Hotel created Oysters Kirkpatrick. Every upcoming restaurant had to have an oyster bar or its equivalent. Paoli’s showcased pantry men setting up Eastern Blue Point oysters on the half shell at $1.50 a plate, steamed Cherrystone clams for $1.75, or shrimp and cracked crab as a tasty snack or as a full lunch or dinner course.20

The focal point of the refurbished restaurant was the venerable mahogany bar. Dedicated to the consumption of hard liquor and wines, the bar was built sometime between 1866 and 1867 for its previous owner, Salvin P. Collins (better known as “Sam”). It was described as a “magnificent” expansive length of highly polished wood upon which drinks were poured, toasts were given, deals were made, and dice were rolled. (At one time, gold nuggets paid for rounds of hard liquor.) Parallel to the mahogany bar was another bar of equal length that was “piled high” with “luscious” meats (roasts, chickens, and game birds), locally grown vegetables, and heaps of iced, freshly-caught bay crabs, shrimp, prawns, and the all-time favorite, oysters. In this era, the “fooderati” could eat their hearts out — the magnificent abundance of California’s vegetables, fruits, fowl, beef, and fish came to market having been grown and raised in uncontaminated soils and waters.

Successful in his restaurant venture, Collins took in a partner, the knowledgeable James Wheeland, to tend bar. Together, they managed their restaurant, making Collins and Wheeland “the place men came to eat” and drink at all hours.21 Women were not included, invited, or welcomed. Instead, women sought respite in their own private parlors, which served afternoon tea as well as sweet sherry and cordials in fancy aperitif cut glassware.

As the kitchen prepared a plethora of foods, the bar offered California and imported wines, ports, sherry, cordials, and champagnes. It was reported that the Jackson Street distillery, A. P. Hotaling, supplied Collins and Wheeland with an average of 55 barrels of liquor a week, making it one of the hottest liquor saloons of its day. The sight of this cooperage lined up in front of C ollins and Wheeland whetted a plethora of appetites and indulgences. And if this was not enough, around the corner was the California Market, described as a “great bazaar” [sic] of delicacies that on foggy mornings served an invigorating breakfast of “oyster cocktails” washed down with a strong mug of coffee.22 Across from Collins and Wheeland was the Mining Exchange, where dusty fortune hunters came to have their gold dust assessed. In all, this corner boomed with the confluence of rough-and tumble activities and exaggerated talk. It would later be the entrance to Paoli’s upscale dining salon, H’s Lordship Room, and the piano bar, The HMS Pinafore Room.

Eventually, Collins and Wheeland died, leaving their establishment to their sons, who passed the business on to other family members. By the 1930s, one chef from the California Market, another Yugoslav whose expertise was the preparation of fresh fish, took over Collins and Wheeland, adding private booths to attract women diners who could avoid a boisterous dining room filled with copper cuspidors (spittoons) and cigar-laden ashtrays.

Over the years, Collins and Wheeland slipped into mediocrity. By the time my parents took over the restaurant, along with the side entrance that had been part of the California Market, Collins and Wheeland was aged and worn.23 The diamond-shaped tile floor was cracked, the Vienna bent-backed chairs were so rickety that they had lost their balance, the white-jacketed waiters with full-length aprons were past their prime, and the smell of stale grease that stuck to the walls like brown glue permeated the place. All that was left was the aging mahogany bar, which badly needed refurbishing.

The Pacific Coast Review, a Financial District journal, wrote a promotional piece at the time of Paoli’s opening. The reporter described that the bar was heavily polished and consisted of 17 stools serviced by four attentive bartenders. The article proclaimed that this vintage bar added the “right touch of age and stability” to the modern décor of Paoli’s.24 Diners who came in with reservations were escorted to their tables; those without reservations were shown to the bar area. As diners began their meals, the bar crowd grew, and to keep these revelers on their side of the restaurant, the bar was piled high with Sterno-fueled silver bowls that kept the heavily seasoned appetizers, lavished with freshly grated Parmigiano cheese and salt, warm. (After all, there is nothing like salt to stimulate one’s thirst and keep the bar crowd drinking.) Like C ollins and Wheeland, which offered the ladies private booths, Paoli’s initially offered the ladies free drinks during a designated cocktail hour to attract their male counterparts. The hottest drink was Pisco Punch, San Francisco’s historic concoction, famously mixed by Alfredo Michele, known to all as “Mike.”

Mike had worked for Duncan Nicol, the overseer of the Bank Exchange bar at the corner of Montgomery and Washington Streets. Secretive about this Peruvian-based brandy drink that reportedly “went down like nectar and came back with the kick of a Missouri mule” (meaning that anyone who drank it seemed to float “in the region of bliss of hasheesh and absinthe”), Mike learned Nicol’s mix. Spying on Nicol, who always made the drink to order behind a locked grate, Mike watched which bottles Nicol took with him to brew the punch. Mike finally worked out his own version of the drink, telling people to “Just call it Pisco Mike’s Punch.” Those who drank it said it was “near the original Pisco Punch” that Nicol had created.24

The hors d’oeuvres never seemed to stop. Paoli’s opening chef, the Dutch Marten Van Londen, had apprenticed in hotels and restaurants and had also worked on the Holland-American Line, where he developed his skills as a pastry specialist. But it was his masterful creation of hors d’oeuvres that made Paoli’s an eagerly-sought rendezvous for the cock tail hour.25 Each succeeding chef de cuisine continued these offerings. With more customers coming in for the cocktail hour, which extended well past the time normally reserved for a bar business, the initial offering of elaborate hors d’oeurves eventually gave way to what was left over from lunch. From 3:30 pm until closing time, a variety of food items such as lasagna, calamari squid (heads and all) planked ground-round steak, Idaho potatoes sliced extra thin, and any food that could be battered and fried were destined for the bar. Some of these items were kept piping hot in silver dishes suspended above Sterno flames. One bartender overheard a woman say to her friend that this “hot stuff ” [under the heated dish] must be delicious as she reached for a flaming ball of Sterno. The bartender quickly repositioned the hot dish. But it became the locker-room joke for years that customers would eat anything that was hot.

Many tantalizing dishes made their way to the bar, but it was the humble zucchini that made it big. In Dad’s journal, the recipe was immortalized. He cut the zucchini finger size. Then they were salted to sweat out their cellular water, floured, dipped in egg batter, rolled in finely ground bread cr umbs, deep-fried, and finally sprinkled with freshly grated imported Parmigiano cheese. They were “to die for.” Platters and chafing dishes were piled high with these steaming sticks, which were washed down by more drinks. Many years later, Pacific Southwest Airlines contracted with Paoli’s to provide these zucchini appetizers. However, the airline did not have the culinary technology to keep these simple but delectable vegetables warm in flight. Certainly, flight attendants tending to a deep-fryer as oil splattered over the cabin would defy the FAA safety code. Even worse, the zucchini sticks would end up as soggy fried food tasting of old, deep-fried oil.

As drinks were passed hand over hand from the bartenders to thirsty drinkers, Paoli’s dining room hummed with captains and waiters attending to their diners. Appetizers were brought to tables in silver serving stands with glass sectionals known as merry-go-rounds, featuring an assortment of marinated foods, including mushrooms, smoked herring in sour cream, crab or prawns, and Caponata (egg plant salad). At the Oyster Bar, shellfish, flown in fresh daily from the Atlantic Coast, was prepared to order with fresh prawns, shrimp cocktails in a spicy sauce, and cracked crabs—when in season. The kitchen’s charcoal broiler specialized in thick cuts of Idaho grass-fed beef grilled under intense heat with sizzling grill marks topped with maitre d’hotel butter. As the commentator for Fortnight wrote, “the care taken over the broiling” of meats with “hickory” charcoal “creates an aromatic heat which seals in the juices.” The aroma of this process lured the lunchtime crowd hankering for chops and steaks.26

But more was on the menu. The signature dish was oven-baked cannelloni. Paoli’s chef, Tony Ancini, blended veal, chicken, and fresh ricotta, spread this mixture onto freshly made crepes (not the commercially made pasta shells), rolled the crepes, and then topped them with a light tomato sauce and a pinch of fresh basil. The cannelloni were a hit for lunch and dinner. Other staples on the menu were house-made gnocchi, handmade tortellini floating in a savory consomme, red sauces and a creamy white sauce base for Fettuccine Alfredo, a hearty minestrone, and white clam sauce with linguini. At the end of the day, a stock pot of leftover minestrone was sent to St. Anthony’s Dining Room.

There was one soup that never made it past the kitchen. It was the creative concoction of a day cook whom Dad had told to “do something different” with the soup. So, the cook added blue food coloring. The startled expression on Dad’s face was memorable as the kitchen staff froze, waiting for his reaction. The soup was dumped.

The “doggy bag ” was introduced during the height of World War II in 1943 by San Francisco eateries promoting “Pet Pakits” to encourage pet owners to feed table scraps to their pets.27 Paoli’s had wax-lined paper bags labeled “Bones for Bowser.” An attending waiter once overheard a little girl ask her parents, “Oh! Are we getting a dog?” when they had asked for a doggie bag. The exchange became an item in Herb Caen’s column.

Paoli’s was popular and an upbeat place to mingle, but its evolution as a premier meeting place was not accidental. My dad was a handsome six-footer, with a physique sculpted by his lightweight boxer days. He was a Dolphin Club swimmer who never missed the yearly swim to Alcatraz. At other times, he dressed à la Robert Kirk Ltd., always wearing a fresh miniature carnation in his lapel, courtesy of his father, who grew them. Early in the game, he figured out the social drill for success; he had a phenomenal memory for faces and names that enabled him to greet each customer by name, even when he had met him or her only once. Relying on charm, good looks, and expertise, he easily manned the maitre d’ station. Appropriate in those days, he used a microphone to announce to the waiting diners, “Mr. So-and-So, your table is ready.” But, more importantly, he quickly learned to extend his arm to the “Mrs.” of the family and escort her with her family in tow to their table, making her the focus of his attention. The ladies loved it.

The restaurant eventually outgrew its initial floor plan. Over one weekend, from its close on Friday night through Saturday and Sunday afternoons, when the restaurant was closed for lunch, the mezzanine office was transformed into a dining room. Plush booths surrounded the periphery of the room with tables for twos and fours in the middle. One time an unassuming couple who were honeymooning were sitting at one of these tables. They enjoyed watching, as Dad described, “the flying waiters who missed their steps as they went up the mezzanine” balancing heavy trays of food. The couple was Juan Carlos, the future king of Spain, and his bride, Sophie of Greece. Ten years later, the Princess Sophie accompanied her mother, Queen Frederica of Greece, to Paoli’s, but this time she dined in one of the private rooms, H’s Lordship Room.

The mezzanine hosted other glitterati of the day. Rocky Marciano, the undefeated heavyweight champion of the world, “spent many nights having dinner at Paoli’s.” Dad wrote that Marciano’s usual order consisted of two top sirloin steaks. He ate the first one, while he “just had the blood” of the second. Dad would spend two weeks with Rocky at his Calistoga training camp working out with the champ and his sparring mates, and trying to keep up with him as the team jogged along the Silverado Trail. Dad wrote in his journal that the boxer knew every stone and pebble along the 12 mile stretch of road and deliberately “kicked” them out of his way to avoid twisting his ankle. Continuing with this memory, Dad wrote that keeping up with Marciano at “his regular cadence” nearly caused “my heart [to give] out… but . . . Hell, I would have died if I couldn’t keep up with them.”28

Marciano died when the small plane he and some of his team flew in crashed in inclement weather. This loss of this friend only exacerbated Dad’s fear of flying. Years later, when Dad befriended the comedian Red Skelton, he was invited to Hollywood to play a nonspeaking role of the trainer in a Cauliflower McPugh scene. Dad drove to and from Hollywood, taking home with him a pair of cufflinks with the comedian’s image.

A silkscreen portrait of another heavyweight boxing champion, Bobo Olson, hung over another mezzanine booth while the local boxing trainer, Lew Powell, was honored with his own corner. Powell had trained a “a dark haired, good-looking kid” with a “natural left jab” who had speed and “knew how to pull away from, or slip, punches.” This kid took the name of “Rocky Ross” but never fought professionally. This kid’s mother was my grandmother. She refused to give permission for her son to turn pro. So on and off, Dad sparred with champions at their training camps. He never relinquished his membership in the Northern California Veteran Boxers Association.

A Holiday magazine photo showed “important” people in San Francisco, including Mayor George Christopher in the foreground and others on the cable car. From left, Joe Paoli; baseball great Frank “Lefty” O’Doul; restaurateur and writer Barnaby Contrad; model Lily Valentine; press agent Don Steele; polo-playing Charlie Low, owner of Forbidden City; advertising executive Howard Gossage; and columnist Herb Caen. Author’s collection.

Over the years, other guests graced Paoli’s, entering through either the Montgomery Street or California Street entrance. San Francisco’s mayor, George Christopher, hosted Queen Frederica of Greece and Princess Irene in H’s Lordship Room. Princess Irene was a strict vegetarian, but the other members in her party ate roast saddle of lamb. The princess was presented with “12 different vegetables cooked different ways,” wrote Dad, who was rewarded with a “kiss from Irene and Sophie.” That was small recompense for Dad having spending that morning culling for appropriate recipes after hearing from the mayor’s office that Irene was a vegetarian.

From Hollywood came actors and actresses. The swashbuckling Errol Flynn hosted a party with the hope of enticing guests to support the Cuban revolution. He was followed by the very handsome James Garner of Maverick fame; Robert Young, whose family owned a vineyard and winery in the Alexander Valley; Gregory Peck, with his mellifluous voice; and pop singer Rosemary Clooney. All of these stars autographed backsides of the restaurant’s penny postcards. Tarzan, aka Johnny Weismuller, talked Dad into a trade: lunches for a song — a song bird, that is. The bird was a Panamanian parrot named Lolita, who sang arias. What Weismuller had failed to mention was that when the bird wasn’t singing, she made a piercing shrill that brought complaints from our neighbors. (Dad was not permitted to trade out lunches again without our knowing what the rate of exchange was.) Another Olympian left a less volatile gift, a photo of himself in his rowing scull, writing from one “water shoveler” to another, signing it “Jack Kelly, Olympics 1920.” Kelly, a triple Olympic Gold Medal winner, was revered as the most accomplished American oarsmen of his day. He was later known as the father of actress Grace Kelly, who would become the Princess of Monaco.

Dad’s journal included other celebrities, as well: singer Vic Damone, who “liked pasta with butter and parmesan cheese; Harold Smith of Harold’s Club, Reno, who took home five pounds of roasted candy coffee beans – a specialty of the house; actress Yvonne de Carlo, who “ate everything” yet maintained “quite a figure”; music composer David Rose, who loved the Emperor’s Desire (strawberries in Blue Nun with sautéed orange rinds, sugar, Grand Marnier, and cognac – all set on fire and then topped with two scoops of vanilla ice cream); Satchmo Louis Armstrong, who liked double-cut broiled lamp chops with fried potatoes; and song writer Jimmy McHugh, who tended toward the marinated artichokes and mushrooms, cracked crab, and sour cream herring.

Then there was the very talented singer and actress who had sneaked into San Francisco, sat in H’s Lordship Room, and ordered Steak Diane for lunch. The maître d’, Emil Brossio, expertly prepared it tableside, and when he presented it to her, his eyebrows knitted together and his eyes rolled heavenward when Barbra Streisand asked for ketchup. When Emil retreated to the kitchen, it was reported that the staff gave him CPR.

When opera diva Licia Albanese came to open San Francisco’s opera season, she was feted in a private room where it was reported that the “great one” had gobbled “great gobs of what she calls ‘Southern Italian food’” at Paoli’s. “You know,” quipped Herb Caen, “puppies a la Milanese.”29 From another corner of the show business world came the first televangelist, Emmy Award winner Catholic Bishop Fulton J. Sheen, whose calming demeanor was testimony to the title of his weekly show, Life Is Worth Living, which ran from 1951 to 1957. He penned prayerful good wishes on a penny postcard that has long been lost.

By the mid-1950s the restaurant had expanded, adding the HMS Pinafore Room, a classy piano bar that featured a wall-sized trompe l’oeil of the Admiral of the Queen’s Navy. The bartenders dressed in period sailor costumes based on the Gilbert and Sullivan operetta H.M.S. Pinafore, which Dad adored. Crystal bar glasses engraved with the names of frequent customers were placed in full view on the back-bar, ready for each special customer, along with specialty ceramic goblets that featured themes reminiscent of the South Seas. Every time Dad walked into the room, the pianist played “Monarch of the Seas.” While other restaurants capitalized on the exotic experiences of World War II soldiers and sailors returning from the South Seas, the Pinafore Room served strong rum punches in fantastical ceramic goblets with floating flowers against the décor of an English operetta. The room was a great success.

The success of the Pinafore Room heralded an upscale and sophisticated dining room called H’s Lordship Room. It was really “His Lordship Room,” but Dad insisted on the British spelling, emphasizing the h and s and dropping the vowel for what he thought represented a more authentic version of a British sailor’s accent. We didn’t question his rationale, as the room was his idea. Red leather booths surrounded the room with a service table in the center. The ceiling was arched with heavy beams made to resemble the inside of a captain’s cabin. Hurricane candles sat on all tables, and a black wooden statue of a Moor greeted the diners. Every detail was perfectly executed according to the nautical standards of an English frigate. On opening night, guests were welcomed aboard with a piper’s lively tune while a drummer dressed as a sailor in period costume tapped out a rhythm, announcing each set of guests on the deck of seafaring dining room that would never sail.

In this room, diners were far from the hustle and bustle of the main bar and the merriment of the Pinafore Room. Service carts with heavily starched red skirts and chafing dishes and silver service embossed with the Paoli family coat-of-arms rolled from table to table. One evening the captain, Victor Bennett, dressed in his finery, rolled a cart filled with all of the ingredients required to make a dish to order tableside. He over shot the chafing pan with the liqueurs. The alcohol in the Courvoisier hit the heavily starched fringe of the table linen and the linen burst into flames. Busboys busily ushered the flaming cart through the exit doors onto California Street, where the fire department was on hand to douse the flames.

Victor Bennett wrote several best-selling cookbooks, including Chafing Book Magic,30 with all featured photographs taken in the H’s Lordship’s Room.

Reading the menu of the H’s Lordship’s Room is to drool – not only about the food but the prices. The 24-inch-long menu included appetizers, soups, and entrees served with an herb salad. Wines and desserts were priced in an accompanying menu. The highest-priced entrées were beef, beginning with a Double New York Steak Gourmet at $8.50 per person. Chateaubriand Richelieu for two was available at the same price. Of course, for diners who wanted the show-of-shows with their entrée cooked at the table, there was the traditional filet, butterfly steak, Vesuvio Flambé with Cognac for $8.50.

Lesser entrées were the Abalone Steak Sauté Supreme at $6.50; Fresh Frog Legs à la Provençale at $6.75; and fresh fish and seafood, which went for between $6.00 and $7.00. The higher priced à la carte entrées were Tournedos of Beef Rossini and Butterfly Filet Steak Diane, and Cognac Flambé — all at $6.85 per person, unless you ordered the Planked New York Sirloin Steak Bearnaise, Rack of Lamb, Chateaubriand, or the New York Steak Moutarde à la Cliff at $7.75 per person ($15.50 for two). The lowest-priced entrée was Chopped Sirloin Steak (a hamburger) at $3.75. Fish, chicken, and veal were $5.00 or less, unless you craved imported Langouste Buerre (lobster tail with butter) at $5.25.

These were the days when meals ended with a flaming dish described as a “flambé” of Crepe Suzettes, Grand Marnier Soufflé, or Cherries Jubilee. The specialty of the house was French Pancakes Balzac filled with diced pears in a pastry cream flavored with green chartreuse liquor priced at $5.50—for two! Butter, cream, and alcohol were not spared in the name of cholesterol or calories consumed. And sweet butter was in every dish.

The wine list began with a brief discourse that explained how wine appealed to the senses and some rules about the variety of wines. Dry white wines would taste better before red wines, and the great wines taste best when they follow lesser ones of a similar type. Tart dishes and highly spiced ones could spoil the taste of wine, and a sweet dessert would destroy a dry wine, although champagnes, sauternes, and Barsacs could be the perfect accompaniments to some desserts.

Holiday magazine dedicated its entire April 1961 issue to San Francisco and, as the saying goes, the game was on as to which restaurants would be written up and which excluded. The spokesman for this edition was San Francisco newspaper columnist Herb Caen, who wrote that, “It’s a tribute to the first-rate restaurants of San Francisco that the dinner hour is still the most exciting time of the day.” Continuing, Caen wrote, “San Francisco has about 2,000 eating places, give or take the meal-a-minute assembly lines [local chains of coffee shops]. A few of them are among the world’s best. A few undoubtedly are among the world’s worst. In between lies a hard core of bustling restaurants whose batting, or fattening, average is several choice cuts about the national average. . . . The reason San Francisco restaurants maintain such a high average is, I think, because San Franciscans know food and demand quality.”31

Caen listed what he considered San Francisco’s good, better, and best restaurants, breaking the list into “five sections: Fancy and Expensive; Very San Francisco; Hale and Hearty; Colorful, Amusing, Exotic; and Notes on the Back of My Menu.”32 Paoli’s was in the category of “Hale and Hearty” and “moderately to expensively priced.” Caen described Paoli’s as a “hustle and bustle” restaurant that meandered from the bar with its “unbelievable crush of Montgomery Street types,” whom Caen compared to the Madison Avenue workforce, to the dining room that served “very good food indeed” under the auspices of the retired chef of the Palace Hotel, Lucien Heyraud. Caen concluded that Chef Heyraud, or Lucien as he preferred to be called in his retirement, was a “far-sighted” appointment.31 As Dad wrote in his journal, he had the good fortune to “hire great chefs” but he did not consider himself a chef. Instead, he thought of himself as a purveyor of fine foods and wines, a modest description that suited him.

Lucius Beebe, a veteran figure in San Francisco’s history, described Lucien as an “unhandsome person” who was “one of the last living repositories of the grand manner of gastronomy as it was lived in the Golden Age not only in San Francisco but in the rest of America.” Lucien had a father-and-son relationship with my father. My dad described the short, rotund Lucien as a “cherub.” Dad respected his expertise, his savoir faire, and his having achieved the coveted crown bestowed by the culinary world, the black hat toque, its highest honor.

Lucien began his career at the bottom, starting as a potboy and apprentice at the Maison Bernard in Lisbon, Portugal, where his father worked. Later he worked in the galleys of the English Castle Line ships; did a stint with the French army for several years; and finally made his way as a saucier on the While Star Line’s Majestic as he crossed the Atlantic. In New York, he cooked at the Commodore, the Colony Club, Hotel Madison, and then the Stork Club. His break came in 1935 when the chef and Baron Edmond A. Rieder of the Sheraton Palace sought him out and made him the highest-paid chef west of the Mississippi. Lured by Michael Romanoff to Los Angeles, Lucien moved south, but he was unhappy among the glitterati and returned San Francisco, proclaiming that his “work has been my life, and to be chef at the Palace is enough for any man.”32

In was in the downstairs kitchen of Paoli’s that the famed Julia Child came to visit Lucien. A stickler for perfection, the home-French chef sat watching the veteran chef as he put the finishing touches on a Christmas Buche du Noel, a chocolate cream cake resembling a holiday log. As Lucien worked, Julia was heard to say that she didn’t want him to exclude any of the traditional steps. Lucien, who always smoked a cigar as he worked, replied curtly, having run out of patience with her needling, that he knew the recipe very well. As they sparred back and forth, the black and white ash that had lengthened at the end of his cigar fell onto the Buche like a mixture of snow and soot while Lucien was heard to say, “But, Madame, I have done it correctly.”33

The competition between restaurants continued. In 1963, Holiday magazine published another San Francisco restaurant guide, a less ambitious accounting of culinary doings among the city’s restaurants. Only five San Francisco restaurants were listed; Paoli’s made the cut. There were no two ways about it: Either diners liked Paoli’s or they did not.

There were no tepid or half-hearted opinions about Paoli’s on the part of the San Franciscans we met. Either they were wildly enthusiastic or downright denunciatory. From the crowd we watched there one evening, the Paolites seemed to be extrovert types—broker’s men, jovial wheeler-dealers, crew-cut young executives and young career gals who sipped double Bloody Marys and talked about “the rat-race.” The huge menu is packed to the margins with dishes often encountered in San Francisco. There were Italian pastas in shoals, as well as Bay shrimps and jumbo pawns, Pacific crab and lobster, broiled scampi, rex sole, abalone steak, breast of chicken a la Kiev. Perhaps the most important to the typical guest was the New York cut of sirloin or Chateaubriand with sauce béarnaise. The portions are generous, the waiters chatty and familiar of manner, the fun infectious if you are handicapped by constitutional stuffiness. Good wines. Expensive.34

Paoli’s made the 1964 and 1966 editions and, whatever the critics said, prided itself as a gourmet haven set in an atmosphere of elegant dining. Paoli’s even took advantage of that description in the yellow-page ads for all those who thumbed through the telephone book looking for good value.

By the mid 1960s, most restaurants had public relations people who promptly fed stories to columnists on a daily basis and were paid dearly to organize special events. However, unsolicited by any public relations effort, two unexpected accolades came to Paoli’s in 1965 and 1967. On Sunday, September 5, 1965, the San Francisco Examiner comic section led off with Walt Disney’s Donald Duck. The comic featured Scrooge McDuck buying a pizza factory named “Paoli’s” and renaming it “McDuck’s Pizza” because Paoli “was using too much pepper,” as McDuck said to his nephew, Donald. One of the cartoonists had been to Paoli’s, and the cartoon strip was considered a plum of publicity that was distinctly different from the gossipy items written by the city’s many columnists. The other piece appeared in Time magazine the week of September 15, 1967. The featured essay, “The Pleasures & Pain of the Single Life,” told of single men and women who chose big cities as their “habitat” and were attracted to “dating bars.” The essay named New York’s Mr. Laffs, Maxwell’s Plum, and Friday; Chicago’s The Store; Dallas’s TGIF (Thank God It’s Friday); and San Francisco’s Paoli’s.35

Competition continued with coveted Michelin stars, which Paoli’s never received. Instead, Dad had his family crest embossed on all the menus in gold foil.

By the mid-1960s, Paoli’s was on the verge of change. The diners who had made Paoli’s popular had begun to age. People became less tolerant of elbowing their way toward a boisterous bar. Others learned more about foods and wines, and as restaurant critics gave their ratings and the industry gained professional status, tastes began to change.

My parents acquired a neighborhood bar and eatery known as The Old Library on lower Clement Street. They renamed it Paoli’s Library, but it drained their energy, so they sold it. The neighborhood ventures were not for them. Most of my father’s competitors had retired, while a few seriously upscaled their operations. But they all knew that there was a new kind culinary style in the making. A new generation of restaurateurs and chefs were on the rise—and they did not tip their toques to the oldsters.

Unlike the hit song “Let the Good Times Roll,” the good times confronted the downward spiral of the economy that rolled into the Great Inflation of 1970. Paoli’s lost its lease on Montgomery and California Streets and moved. As my parents exited Paoli’s for the last time, my mother walked through the Pinafore Room and ordered that a case of deep red tomato paste be pulled off the moving trunk and that the cans be opened. Facing the magnificent trompe l’oeil that caricatured the admiral of the Queen’s Navy, she aimed for the old gent’s monocle and plumed hat, and after targeting them, she let loose with the paste, bull’s-eyeing the corpulent physique. It was a true Hollywood ending as red paste dripped down the gold background. My mother was determined that no one would peel him off the wallpaper. No one would ever own him.

My parents had acquired a PG&E substation known as Station J at Montgomery and Leidesdorff. They temporarily rented the space to a disco bar. This space eventually became the location of the “new Paoli’s.” But it was not the same. The vintage mahogany bar would never be replicated, and with it went the memories of those generous piles of hot hors d’oeuvres. The two-or three martini lunches, the generous executive expense accounts, and the relaxed lunch hours were relics of the past.

New Paoli’s closed on June 30, 1984. Dad died on January 26, 1996, leaving a legacy among his peers and Paolites that was summed up in another famed restaurateur’s obituary, Lorenzo Petroni, who “learned the art of restaurant promotion from Joe Paoli, considered by some to be the best in the business.”36

About the Author

Deanna Paoli Gumina is a native San Franciscan and a graduate of the University of San Francisco. She was the assistant archivist under Gladys Hansen, the founding archivist of the San Francisco History Center at San Francisco’s Main Library. Dr. Gumina has published articles in the journals of California History, Pacific Historian, The Argonaut, and Studies in American Naturalism, and is the author of two books. Dr. Gumina is a psychologist in private practice in San Francisco specializing in learning disabilities.

Dedication

This article is dedicated to my parents, whose hard work helped to elevate the status of restaurant work as a skilled profession.

Notes

- Herb Caen, “Handbook of San Francisco Restaurants,” Holiday, April 1961, 29:4, 167. (Henceforth cited as Holiday, 1961.)

- Curt Gentry, The Last Days of the Late Great State of California (New York: Ballantine Books, 1968), 312–3.

- Andrew Hurley, Diners, Alleys and Trailer Parks: Chasing the American Dream in the Post War Consumer Culture (New York: Basic Books, 2001), 41.

- Waverly Root. The Food of Italy (New York: Random House, 1971), 473, 379.

- “The Los Angeles Times Vintners Tasting selects Robert Mondavi Winery 1969 Cabernet Sauvignon as the Top Wine,” Robert Mondavi Winery website, Napa Valley, link: About Us.

- Ruth Thompson and Chef Louis Hanges, Eating Around San Francisco (New York: Suttonhouse Ltd., 1937), 93–94.

- Jerry Flamm, Good Life in Hard Times: San Francisco’s 20s and 30s San Francisco: Chronicle Books, 1978, 53.

- Doris Muscantine, A Cook’s Tour of San Francisco (New York: Charles Scribners’s Sons, 1963), 214.

- Joseph (Joe) J. Paoli, personal journal, family scrapbook collection.

- James Benet, A Guide to San Francisco and the Bay Region (New York: Random House, 1963), 13.

- Holiday, 1961, 167.

- Paoli, personal journal, family scrapbook collection.

- Muscantine, 338. Thompson, 62.

- Peter Moruzzi, Classic Dining: Discovering America’s Finest Mid-Century Restaurants (Layton, Utah: Gibbs Smith. 2012), 10.

- Root, 326.

- Root, 7, 18–9.

- Moruzzi, 10.

- Family scrapbook collection: “Billingsley Wants Paoli Pepper Mill.”

- Moruzzi, p. 24. Rita Paoli interview, 2013. Accessed via the Internet: House of Murphy menu.

- Moruzzi, p. 15. Family scrapbook: “Popular Paoli’s.” Fortnight California’s Own Newsmagazine, August 18, 1954, Vol. 17, No. 4, no page reference. Family scrapbook collection.

- “The Inner Man,” Schellens Collection published by the San Mateo County Genealogical Society, 2007. Heinemann, “Western Whiskey: Saloons & Retail Mechants,” Winter 2006, 28. Internet. Thompson, 47.

- Schellens Collection. Muscantine, 8.

- Thompson, 46–8.

- “Paoli’s,” The Pacific Coast Review, November 1952, family scrapbook collection.

- Ibid.

- Family scrapbook: Fortnight.

- Wikipedia: “Food and Think” Internet website “Unwrapping the History of the Doggy Bag,” December 21, 2012.

- Diary. Family scrapbook and clippings, Dick Nolan, “The City,” San Francisco Chronicle.

- Family scrapbook and clippings.

- Victor Bennett and Paul Speegle, Chafing Dish Magic (San Francisco: Hesperian House, 1960). See other books by Victor Bennett, including Around the World in a Salad Bowl (New York: Collier Books, 1961) and Papa Rossi’s Secrets of Italian Cooking (New Jersey: Prentice Hall, 1969).

- Holiday, 1961, 167.

- Lucius Beebe, “Lucien of the Palace,” Holiday, March 1958, 23:3, 95.

- Interview, Rita Paoli, 2013. This has been one of my mother’s favorite stories about Lucien.

- “U.S. Restaurants,” Holiday, June 1963, 33:6, 119.

- “The Pleasure & Pain of the Single Life,” Time, September 15, 1967, 90:11, 26–7. Walt Disney, “Donald Duck,” San Francisco Examiner, September 5, 1965.

- Obituary, Lorenzo Petroni, San Francisco Chronicle, June 2, 2014. (Accessed via the Internet.)

- William Branson, “Secrets of Pisco Punch Revealed,” California Historical Quarterly, 52:3 (Fall 1973), 236.