by Leonard Stefanelli

The Argonaut, vol. 25 no. 1, Summer 2014

As a third-generation San Franciscan, I still reside here with my wife after 80 years. We have seen many changes in lifestyles, environment, and political infrastructure — and have been blessed with amazing views of hills, a magnificent bay and its bridges, extraordinary dining, and a population made up of every ethnicity in the world. This is a rare and unique city in every aspect, and I am proud to be able to say, “I am a native son.”

I have noticed that while The Argonaut has covered almost every aspect of the City’s unique and special history, it has never referenced the San Francisco’s waste-collection services, possibly because it is not a glamorous or exciting subject, or maybe because no one pays much attention to this service. The City has never been without scheduled waste and/or garbage collection for well over 100 years—except for one day, April 18, 1906. There has never been a work stoppage as a result of labor strife, weather, or any other reason. I became part of that rich San Francisco tradition and history, and I think it would be appropriate for me to share some of my personal experiences, both growing up in San Francisco and being a “scavenger.”

I was born in the Haight-Ashbury District on May 6, 1934, at 1822 Fell Street. When I was three, I moved in with my grandparents, Lenora and Harry Corbelli, who lived in a grand old three-story Victorian home at 117 Cole Street. My grandfather worked for the Southern Pacific Railroad.

My uncle, Pasquale Fontana, lived around the corner at 2122 Grove Street. He was a scavenger who would play an extraordinary part in my future life, starting when he gave me the task of “Collecting the Book” when I was seven years old.

“Collecting the Book” was the individual’s scavenger ’s other responsibility, in addition to collecting the garbage. Each scavenger was responsible for collecting the fees for providing that service. At night a scavenger would ring each customer’s doorbell, and when the door opened, he would say “Garbage bill!” and be paid accordingly; at that time the fee was $1.10 for two months’ service. When I was seven, Uncle Pasquale taught me how to ring the doorbells and make change— probably giving me a better math education than I could have had in school.

Around the corner from my grandparents’ house was Andrew Jackson School, where I attended elementary school. My teachers were Ms. Shea (kindergarten), Ms. Anderson (first grade), Ms. Wendell (third grade), Ms. Daniels (fourth grade), Ms. Sanders (fifth grade), and Ms. Walsh (sixth grade). I have no idea why I remember all these names at this stage in life, but I do, especially Ms. Walsh, who had the worse case of body odor anyone could imagine. Most of us tried not to ask Ms. Walsh too many questions, because when she would come to our desk and look over our shoulder to respond to a question, the odor was severe. It was better not to ask for help.

Myrtle B. Ozer was the school’s principal. I got to know her because I was sent to see her more times than I want to admit, because of “problems” over the years with my teachers (or because of my teachers’ problems with me). I remember a little wooden stool that I would be told to sit on in the corner, awaiting the call to come into her office, dreading and/or anticipating the stern warning of impending disaster if I did not get my life in order.

Cecil Briones owned the Park Pharmacy. Aside from selling medical supplies, the Park Pharmacy had a magazine rack that included comic books. I always enjoyed Walt Disney’s Donald Duck and his three nephews, Huey, Dewey, and Louie. I also liked Uncle Scrooge, who had a swimming pool that he swam in, but instead of water, it held money.

However, one day I did not have the 5 cents necessary to purchase the new edition, so I thought it would be cool to pick up the comic book and walk out the door without paying. I was promptly caught by Cecil Briones. This was the most embarrassing experience in my short life, and resulted in a lesson I would always remember, one that made me a better man. As life went by, Cecil and I became friends.

The Park Pharmacy also sold books. One day we heard of a very risqué book called Catcher in the Rye. Allegedly, on one page in the book, in bold print, the dreaded “four letter word (f – – k)” was in print. When no one was looking, we picked up the book at the Park Pharmacy. After some lengthy reading, we found the word in bold and brassy print. Wow!

During my two years at Dudley Stone Junior High (I never did learn who Dudley Stone was), my friends and I attended Saturday movie matinees at the Haight Theatre at Haight and Cole Streets. Tickets were 15 cents each. As we sat in the back row, we had our first exposure to the opposite sex. We ate donuts at Metz’s Donuts next door and played touch football in the “Pan Handle” long before people slept there.

When we graduated from Dudley Stone, some boys went to Lowell or St. Ignatius, either because their families had money to pay for the private school education St. Ignatius offered, or because the kids were smart enough to get into Lowell, which was a free public school with elite academic standards. Don Streltzoff and I were among the others who went to Polytechnic High School, across the street from Kezar Stadium. I thought I wanted to be an auto mechanic, and Poly High had great auto mechanics, woodworking, and metal shop classes—plus an excellent football team under the leadership of the famous coach, MiltAxt.

Being fourteen years old, I thought I had the world in my hands. I made lots of new friends—and met girls. I had great times—some bad times, as well. “Poly” had a reputation of having some resident “Muns” (“bad asses”). Because I was short, I was initially picked on—in today’s terms, bullied—on a regular basis.

My grandparents were getting on in years (though they were younger then I am now), and I had a “long leash.” As a result, I started to become a “bad ass” as well. I wore Levi’s jeans with cuffs rolled up, black shirts with white buttons tucked into my pants, a chain for a belt (also a defensive weapon), and a “flat top” haircut with “fenders” combed into a “ducks ass.” Boy, was I a mean bad ass! Nobody screwed around with me! I got in a few fights, drank a lot of beer, chased women (did not catch many),and had fun, fun, and more fun. My first term report card reflected that attitude, five Fs and one D (in gym).

At the time, I had to take my report card to each individual instructor, who would to write my grades by hand and initial them. I then took a pen and made each F look like a B or an A. I did this to satisfy my grandmother, Noni Lenora, who for some reason thought I was special.

Noni was getting older, and I convinced her that she needed someone to drive her around in my grandparents’ 1941 Plymouth sedan. She signed a “need and necessity” form, which allowed me to apply for and receive a Learner’s Permit at age 13½. At 14, I got my driver’s license.

Once I had my license, I put fender “skirts” and musical horns on the car to bring status to my driving skills and make people realize I was the “Cock of the Walk. ”Few kids had a driver’s license, let alone access to a car. Having both resources at my disposal was a great social advantage, but not necessarily conducive to getting a good education.

After such a dismal report card for my first semester in high school, one would assume that I would have attempted to improve the following year. As the record will show, to mitigate that problem, I “applied myself.” In my second term, I was the proud recipient of (count them) six Fs. This time I flunked gym.

During my first year in high school I’d made new friends who helped me broaden my education in “life.” I met some characters who attended St. Ignatius High School and lived near the school some six blocks west of my Cole Street address. Andy McCarthy, John Wurm, and Dick Theise had designed and constructed a “tool” that would open any door in St Ignatius Church. The tool was an 18-inch piece of “catgut,” a form of plastic used to string fish hooks. When we put the cat gut in a pot of boiling water, it would become limp. Then, when we took it out of the water and hung it on the back of a chair to let it cool, it took the form of a “U.” That prepared length of cat gut could release any locked door.

Now, you are probably thinking that we used this “tool” to steal valuable assets belonging to the church. On the contrary, we broke into only one room—the room behind the main altar of the church, where the sacramental wines were stored for ceremonial purposes during the Catholic mass. Once we got the wine, we used the same tool to open several locked doors, eventually gaining access to one of the two tall towers of St. Ignatius church. Overlooking the Bay Area, perched high in the tower, we enjoyed the extraordinary views as we drank the sweet-tasting wine used for mass.

I once asked my Irish friends, who were all Catholic, if using sacramental wine to get a “heat on” was somehow sacrilegious. Their response was simple and logical to wit: “It has not been blessed yet; therefore, it is only wine to drink.” I can only assume that my friends’ logic was correct, because none of us experienced the “Wrath of God” over the incident. But, to play it safe,I only did it once.

Another learning experience was my exposure to drugs. My friend Jimmy Jensick was a drummer. When most of were smoking cigarettes and drinking beer, Jimmy was into marijuana at age 15, which was a rare situation at that time. But, before we knew it, Jimmy had graduated into heroin. He died of an overdose at 16 years of age. To this day, even though I have had ample opportunity to use marijuana and a multitude of so-called “recreational drugs,” I have had absolutely no desire to use them under any circumstances. Not even cigarettes, which I gave up in 1970; this was another learning experience growing up—and a valuable one.

Jimmy’s death was a turning point in my simple life. I saw that as a result of all my fooling around, I was now a year behind all the people I had started school with. For the first time, I realized that life was passing me by.

I was to understand later in life that every individual who has attained the age of 18 (typical graduation age from high school) is not always mentally equipped to learn, gain, appreciate, and respect education—surely, I was not. I attempted to apply myself, but I surely was not at the head of my class. I did graduate four years later, but only after Paul Hungerford, the Dean of Boys at Polytechnic, took a liking to me. He allowed me to take the civics test four times, finally passing the course and acquiring sufficient credits to earn a diploma. Wow!

As graduation day neared, after spending five years in a four-year curriculum, I was called into Dean Hungerford’s office. He sat me down (he was a football coach before becoming the dean) to give me some fatherly and “brutally frank” advice, evidently because for some reason, as I have noted, he liked me.

After a bit of a lecture, he pointed his finger at me and then out the window at Kezar Stadium, philosophically stating in a commanding voice: “Stefanelli, I know you have some “f – – ing brains, but if you go outside in that world, and f__k around like you f__ked around in this school, you will end up picking up garbage!”

And that is exactly what I did at age 19. I went to work at Sunset Scavenger Company, driving my Uncle Pasquale’s Truck #3, serving the neighborhood and the people I had lived and played with since I was born.

As time went by, I realized what Dean Hungerford was suggesting. Simply put, he was reflecting the opinion of most educated people—that the last choice in life for anyone who had to work for a living was to collect someone else’s garbage. In other words, being a garbage collector represented the lowest possible rung on the social ladder.

I did not realize the impact of that statement until later years. What he was saying, is this: “Anyone can be a garbage man, that is, have a strong back, a weak mind, and (an added caveat) do the work of an Italian.” At the time, I did not realize that Dean Hungerford was not deliberately or consciously discriminating against garbage collectors; his statement simply reflected what the average person thought about the men who provided this service.

Work and Courtship

After working for Sunset Scavenger Company for a year, demonstrating that I had the physical and mental ability to become a shareholder and a “Boss Scavenger” in the company, I was allowed to purchase a “share” in 1954 and was assigned to Truck 27 in the Fillmore District. At the same time, I began to date Virginia Campi, the 16-year-old daughter of Guido Campi, a partner in the Sunset Scavenger Company. I got to know my future father-in-law Guido Campi, who was a partner in Sunset. He was also president of the Sanitary Truck Drivers and Helpers, Local 350 Teamsters, so he balanced a unique relationship between being owner of the garbage company and president of the union.

One rainy night, the International Teamsters Union had a dinner at the Fairmont Hotel. The cost was $10 a plate. The dinner was held to honor Jimmy Hoffa, president of the International Teamsters Union. Guido Campi asked me to go with him. I was introduced to and shook hands with Jimmy Hoffa that night. Afterward, Guido and I drove to his home in “Dago Alley,” which was the one-block Oakwood Street between 18th and 19th Streets and Dolores and Guerrero Streets in the Mission District.

“Dago Alley” represents a unique but a significant component of scavenger history. At one time, 19th Street did not pass from Guerrero to Dolores. The term “alley” came from its being a one-block street and a dead end; the term “Dago” from the fact that so many Italians, including the Fontanas, Guaraglias, Moscones, Leonardinis, Chissios, Borghellos , Oraratos, and Campis (to mention only a few), lived there. Most of these Italians were scavengers.

At about midnight that night, I parked my car, and Guido and I discussed the fact then in less than four hours, both of us would have to get up and go to work in the pouring rain after we had had a very good experience with “adult beverages” that evening. I figured it was good time to follow the Italian tradition of asking the father to marry his daughter.

I said, “Guido, I would like permission to marry your daughter.” His response was simple and direct: “Ma and I figured that out already, and I respect your decision to ask me first, but let me add this: If you are marrying my daughter for my money, forget about it because I have none. People who have money don’t spend it. I spend my money and, because of that, I do not have any. He added, “I have a roof on my house, food on the table, and no one trying to take it away from me. What else does a man need in his life?”

In later years, I realized what a profound and philosophical thought that was toward life in general. In reality, that was the basic desire of the Italians (for that matter, of any immigrant who came to this country more than 100 years ago).

I responded that it was never my intent to go after his money, and he agreed to accept me as his pending son-in-law. At 4 a.m., with heavy heads (from booze and cigarettes), Guido and I left to work in the garbage business. He walked to his route, and I drove to the company, picked up my truck, and drove to my route in the still-pouring rain.

As an added caveat, when I first saw Virginia at “Dago Alley,” she was helping her dad Guido “picking ducks” that he had shot. Watching her, in that moment, I thought that if I ever got married, that was the style of woman who would fit well into my life.

After some three years of courting, Virginia and I were married on September 5, 1959, after I finished a brief stint in the United States Submarine Service. We have been married going on 55 years, and I am proud to say, she has not picked a duck since we were married. Boy, was I blindsided. (Only kidding, Virginia.)

Virginia and I had our son Joseph almost a year to the date after we were married. The need for paternal responsibility became evident to me, along with the importance of long-range planning, and I concluded that I had to somehow improve my potential, whatever that may be.

I decided to go to University of San Francisco (USF) for two years of night school, where I studied accounting, corporate law, and business administration. Our beautiful daughter Gina came into our life. I thought that I might someday want to do something different with my life, possibly work my way up the corporate ladder at Sunset Scavenger Company. However, as in high school, I had no place to apply the learning I was getting at USF.As a result, I became bored. What I was being taught seemed foreign.

I concluded that, for me, the ultimate educational experience would be to go to school for four hours in the morning, have lunch, and then work in the business I was learning about—I wanted to apply what I was learning in school to my actual field of endeavor—on the same day. What an outstanding educational process, I believed.

I realized that using what I was learning on the same day I learned it would eliminate the boredom of school and mitigate the feeling of repetition associated with reading and oral instruction over an eight-hour period.

I often shared facetiously with friends and associates that I went to USF “twice a day: once to get an education and the second time to pick up the garbage.”

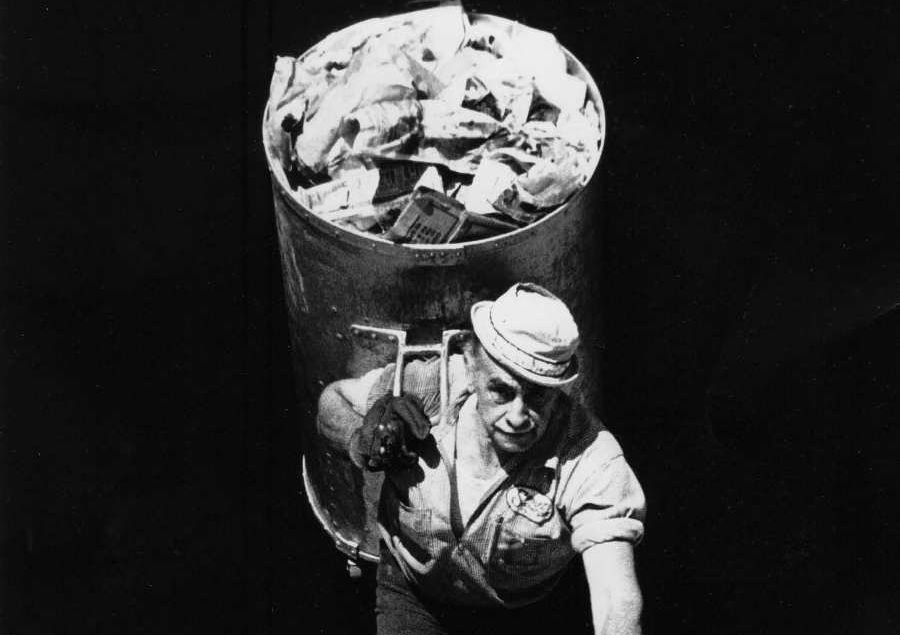

Picture, circa 1950, of the traditional “open truck” that had been used by the company since the turn of the twentieth century; the only “improvement” was that a gasoline engine replaced the horse in 1920. The picture shows Attilo Borghello, Aldo Bacigalupi, Mario Stefanelli (author’s cousin), and Terso Bioni. Terso’s two brothers, Ned and Bob, also worked for the company. Courtesy of the author.

Looking back at the way the scavenger company was founded and still operated in the 1950s and early 60s, I see that I did not have much opportunity for advancement, compared to the way today’s modern waste collection companies are run. Although education was clearly an important tool, there were not many areas within the company where a higher education would be an asset or a resource for advancement. I also knew that oftentimes the “old ways” were in fact the “best ways” to do business, and unless something changed, that would be the order of the day.

In other words, when you became a shareholder, you did the same job as you did yesterday, and then some. You collected the garbage, but as a shareholder you also “Collected the Books,” ringing the doorbells of some 136,000 individual accounts. Working on the old “open trucks” was clearly a backbreaking job. You used a hook that hung off your shoulder to pick up small garbage cans, dump them into a larger 75-gallon aluminum container, and take the load to the garbage truck. Once there, you carried that 100-plus pounds of weight up seven stairs and into the truck’s open body. You dragged or walked the contents over the existing garbage and shook the bags open to recover rags, bottles, newspaper, and cardboard for recycling. Then you jumped on the waste to compact it in the truck.

The job was hard, extremely hard, especially when compared to job of today’s scavengers using today’s equipment. My experience collecting trash for ten years in the Fillmore District can be summarized by this description: I was carrying a can up the stairs and into the open truck on a hot day, dripping with sweat, wiping off my neck the live maggots that fell out of the top of the can I had on my back.

I happened to see a black man on a stairway, staring hard at me. I yelled down to him, “Hey, man, you got a problem?”

“Stay cool man,” he replied.

I yelled back, “Then what in the hell you looking at?”

His response over-whelmed me. He said, “I just never saw any man work like that. I thought Lincoln freed the slaves.”

As long as I live, I will never forget that comment and how right he was. Unless you were there, you cannot possibly understand how brutal our job assignments were, compared to a scavenger’s job today, in the age of modern compaction equipment.

But that was the way scavengers had done business since before 1900. The only real thing that had changed was that now we had a gas engine instead of a horse.

In 1962, as an employee/shareholder of Sunset Scavenger Company, you were a scavenger, a mechanic, or one of three so-called “executives” who worked in the office. There was little opportunity for advancement.

Our job was simple: Drive to the route, collect the garbage, dump the truck, ring the doorbells to collect the money, deposit the collections into a company account, go home, eat dinner, and go to sleep. Then get up and go to work again.

I actually loved working on the truck. I was proud of being a scavenger and had a great crew—Louis Bertone, Pet Guaraglia (my godfather), and Booker T. Day. We worked together like a well-oiled, coordinated, and finely calibrated piece of machinery.

Booker was one of only a few black employees the company had in the early 60s. He was an invaluable resource in teaching me about other matters in life: a side of life that included the culture, philosophy, and concerns of African Americans, and he schooled me in these matters on a daily basis. Very few white people had the opportunity for such an extraordinary educational experience. Booker’s knowledge proved to be a great resource to me in my political and corporate life, which was still to come. The insights I received were further amplified by the one-on-one personal contacts I made on my route in the Western Addition—especially when I rang the doorbells to collect the money due.

On the garbage trucks, we finished a scheduled eight-hour day in five and got paid for eight. That was a benefit of working on the trucks, in addition to working in the open air. We also got a beer or a coffee royal at every bar we had on the route. There were not many of these, but enough to satisfy a thirst.

Because the job was tough, especially on the older members, back, leg, and hip injuries were commonplace, as well as cuts because of discarded razor blades and broken glass. I was only 28 years old at the time, but I saw the hardships of the years ahead. Not only did I realize that there was little opportunity for advancement, but I also could not necessarily envision myself carrying garbage until I was 55, the earliest I could retire.

After my two years of night school at USF, I went to Golden Gate College at the urging of my good friend Joe Picetti, who was in the casualty insurance business. I applied for and obtained an insurance agent’s license from the State of California to sell general insurance, and I went to work for Joe’s company, Agents, Brokers Consolidated: ABC Insurance.

I was compensated by a split commission arrangement, where ABC would take 50 percent of whatever commission on what I sold to maintain the administrative need (billing, claims, and so on), and I would be paid the balance. In three years of selling insurance on the side, I found that I was making more money on a split commission basis in the insurance business than by working at Sunset as a scavenger.

In May of 1965, I was planning on leaving Sunset Scavenger Company for full-time employment in the insurance business when a unique happening at Sunset Scavenger Company changed my life. A stockholder revolt of sorts had resulted in the election of a new board of directors made up of working scavengers. The ousted board members walked out, and during their absence a special election was held. I found myself Second Boss on Truck 27, on Friday, August 27, 1965, and was elected president of the Sunset Scavenger Company on August 28. I was only 31 years old and suddenly in charge of a five-million-dollar-a-year-business!

It would have been a traumatic experience for anyone. But let me say, I survived the extraordinary challenge in large part because of the little bit of education I’d had at USF. When I was in school, I had nothing to apply my learning to, but now I realized that without that education, I would have failed in my new venture. Because of my classes at USF, I could read and understand income statements and balance sheets; comprehend corporate law and business philosophy; and survive in my new position. This experience, plus a dose of common sense and simple logic, proved to be the keys to my success.

When I became president of Sunset Scavenger, San Francisco was facing the impending disaster of not having a place to dispose of waste. Historically, every Bay Area city used San Francisco Bay to dispose of waste. But, in 1970, all bay-fill operations were terminated, including those that filled it with garbage. Sunset Scavenger and Golden Gate Disposal faced the possibility of having the collection services terminate for the first time since 1906.

San Francisco produces in excess of 1 million tons of waste a year and has no physical or legal place to dispose of it. A simple fact of life, which few people in the City realize, is that if you cannot dispose of the waste collected, you cannot collect the garbage, once the garbage truck is full.

At the same time San Francisco faced this crisis, the nation at large was realizing that garbage was becoming a problem. People also realized that garbage collecting was, potentially, a multi-billion-dollar industry. Many people, including large corporations, realized the potential opportunities the industry offered.

The solution? Nobody could change the product (garbage), but people could change the name to a more psychologically and socially acceptable term: solid waste. All of a sudden, the world was overwhelmed with “experts in solid waste,” even though 90 percent of them did not know anything about it, other than to put their garbage cans out on collection day.

It was the scavengers who proposed a solution to the problem of too much solid waste and nowhere to put it. However, the historical stigma of being a scavenger created problems for me as I attempted to deal with the politics of San Francisco. My task was to demonstrate to the politicians and to the newly established “environmentalists” that the people who truly understood the complexities of the solid waste industry were, in fact, the scavengers. Politicians and environmentalists believed the contrary.

We, the scavengers, and others in city government, were getting hammered about the alleged lack of planning and the poor leadership that had led to the pending garbage crisis.

A photograph of the author, taken in May of 1956 at Steiner and Fulton Streets on top of an open truck. Courtesy of the author.

We, the scavengers, had a pending disposal program—to use a site at Sierra Point, which was developed in 1962, to replace the landfill owned by the Southern Pacific Land Company. (The City had used this site since 1906. It was a true sanitary landfill site, diked off from bay waters, environmentally secure, six years in development, and would use $2.1 million dollars of borrowed money.) The plan was being challenged because scavengers—not “Solid Waste Professionals”—were making the proposal. Because of that challenge, the media, some politicians, and many so-called environmentalists were working to discredit our proposal.

We were challenged by the Save the Bay Association to a public debate at the Academy of Sciences in Golden Gate Park. Our PR people and attorneys strongly recommended that I not participate, arguing that “they will tear you apart.” I replied that we “are being torn apart now” by them and by the media, and we needed to respond.

I recall that one old San Francisco Italian, Primo Repetto, advised me with an extraordinary statement: “If you do not blow smoke up your own ass, surely no one else will.” With that thought in mind, and because someone had to “blow smoke,” I agreed to participate in the event. When I arrived, at least 300 committed environmentalists were present, intent on stopping us from using the controversial Sierra Point site. I knew that if they were successful, the garbage collection services in San Francisco would cease. However, no one could relate to that fact and surely no one could comprehend the ramifications of garbage piling up in the City, because the service had never been terminated. People could not even imagine the chaos, the filth, the enormous impact of uncollected garbage.

After some tenuous opening questions and responses, one environmentalist rose and asked me why I, as president of the company, was not using a “magic” system from Japan, where garbage collectors “baled” wastes in cement blocks and then built houses with the blocks. I had not seen the process, but I knew of it, and knew it was surely not a viable solution for a multitude of reasons. My response to her went something like this:

Madam, if you compress solid waste in any environment, it generates methane gas, which is flammable. If you seal the waste in concrete, the “block” could blow up . . . and to mitigate that possibility, one would have to cut holes to allow the gas to be released. If we did this, aside from the release of a combustible gas into your home, you would also have the chance of smelling dead crabs.

With that, I could see that the audience approved of the logic of my response, but the environmentalist did not. She fired back, “Well Mr. Stefanelli, your response is unacceptable . . . and the reason I say that, is, from your own admission you are only a ‘scavenger.’ What is your experience in the solid waste industry to voice such an opinion?”

My response was direct. I shot from the hip:

Madam. Yes, I am a scavenger, and proud of it. But for you to suggest that I don’t know what I am talking about is ludicrous. Until you have experienced the joy of inhaling a fly, feeling live maggots creep down your neck and watermelon juice running down the crack of your ass, please do not suggest to me that I do not know anything about garbage—or about what you refer to as “solid waste.”

The response from the listeners was overwhelmingly positive, amplified by cheers and loud applause. The results were summarized the following day in the San Francisco Chronicle. The front page headline read: “The Great Debate, The Environmentalist vs. Scavengers.” The article stated, “The Scavengers win hands down, led by that handsome young president of Sunset Scavengers.”

This was the turning point. Eventually, the politicians, environmentalists, and the general public began to recognize and, yes, respect our experience and our services, as well as our commitment to the City that we served. As a result, San Francisco today has the most comprehensive, cost-effective, long-range solid waste program in the world.

Today, San Francisco’s garbage disposal system includes the world’s largest solid waste transfer station, a materials recovery facility, as well as other related facilities that receive and process the one million tons of waste generated annually in the City.

Enhanced by multitudes of waste diversion and waste reduction programs, composting, and recycling, the current company continues the efforts to enhance and create new programs for the City and perpetuate the programs the scavengers began well over 100 years ago. Less than 40 percent of the waste generated requires landfill today.

Myron Tatarian, director of Public Works, was quoted in 1970:

San Francisco has the most advanced and comprehensive solid waste management program in the world, and that occurred because the City of San Francisco, with its legislative authority, recognizes and respects the vast experience, dedication, and commitment that the scavengers have provided the City and by each party’s recognizing and respecting what each offers the other, the City and the rate payers are the benefactors.

As a native son, who still lives here in the City, in my sixtieth year active in this business, I am extremely proud to have been a scavenger and proud of the company that I and so many other scavengers helped to build. That company, now called Recology Inc., is still providing that service, currently under the able and professional direction of Michael Sangiacomo.

Mike Sangiacomo, the son of a scavenger, is by profession a Certified Public Account. He prefers not to be called “Michael” because that is what his mother called him when he was in trouble as a young man. We became associated in 1982, while he was the CFO of the Pacific International Rice Mills. At that time, I am proud to say, I retained him as my chief financial officer to meet the growing demands of an ever-expanding and complex business and the challenges associated with it. We worked well together until 1986, when I left the company for other opportunities in the solid waste industry, eventually going into semi-retirement at age 73.

Mike eventually became president, when Sunset Scavenger and Golden Gate Disposal merged under the name of Norcal Waste Systems Inc. He once publicly referred to me as his mentor, and when I retired some years ago, he extended an invitation for me to become the company’s senior advisor and consultant, which I considered to be the ultimate compliment and honor.

So, as I enter my sixtieth year of activity in the solid waste (garbage) industry, thanks to Mike and his board of directors, I have come full circle. I returned to the company and the industry that gave me a job and allowed me to build from that job a long and satisfying career. Through circumstance and hard work, I helped it mature, grow, and earn the public’s respect. All of this was made possible by the roots created by the Italian immigrants who made it all possible. A record that began well over 100 years ago, when Italian immigrants came to San Francisco, could not find work because of discrimination and had no welfare benefits, and went into a “service” business that no one wanted. This is a record that Mike Sangiacomo, myself, and all the scavengers of San Francisco were and are proud of to this day.

About the Author

Leonard Stefanelli, a third-generation San Franciscan, was born in 1934 in the Haight-Ashbury District of San Francisco. He attended Andrew Jackson Grammar School, Dudley Stone Junior High, and Polytechnic High School. Upon graduation in 1953, he started working at Sunset Scavenger Company on the route his Uncle Pasquale operated. In 1965, at age 31, Leonard became present of Sunset Scavenger Company, and served in that capacity for almost twenty-one years, until 1986. He now works as a consultant to Recology Inc. and is in his sixtieth year in the “scavenger” industry. Leonard is currently writing a memoir of his experiences in San Francisco.